The Collective Intelligence of Teams

Go deep with the whole playlist

In 2015 Anita Williams Woolley and colleagues published some groundbreaking work understanding the ‘collective intelligence’ of teams.

They asked ‘can we judge the cognitive power of a certain group of people?’

The answer was that yes, they could and also there were certain things that helped predict this collective intelligence.

Professor Woolley explains the part that gender plays in this team intelligence and then gives you a test that you can take to help predict collective intelligence in your own teams. Anita’s work is fascinating and immensely thought provoking. Is it time to change your team?

You can take the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test here.

TRANSCRIPT

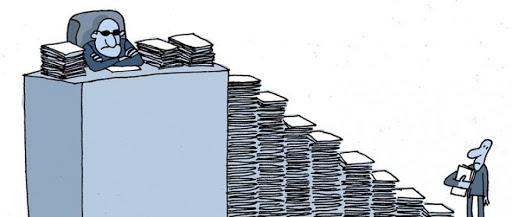

Bruce Daisley: So here’s the story. This is a podcast about making work better now. Maybe that’s partly about improving work culture and also it’s a little bit about making our workloads feel more manageable, just trying to reduce the amount of stress we’re feeling.

If you wanna do a good deed, today’s episode’s actually a really good one, and uh, it’d be a good one to share. Why don’t you forward it to someone at work? Good for the all round karma. You know what I mean? Today’s episode. Is looking at the research into what makes good teams. And I saw some research by Anita Williams Woolley this time last week.

I spent all day on Sunday watching her Ted Talks and her lectures just sort of devouring everything she had on, on YouTube and the internet. And I contacted her with a question about some of her slides. Uh, she basically got back to me and agreed to come on the, the show. So Anita Williams Woolley is an associate professor of organizational behavior.

The temper business school, that’s part of Carnegie Mellon University, and of course that’s in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Anita’s work is to try and understand the idea of collective intelligence. That is in the same way that IQ measures individual intelligence, she found a way to measure the intelligence of different groups.

And the fascinating thing is they found that the different groups, different compositions of people, tended to show the same collective intelligence across different puzzles. Right, so she saw that she could measure it and predict it, and obviously that would be really interesting for any of us who are responsible for being in teams or creating teams.

Her and her colleagues found a couple of things that you’re gonna find fascinating about team construction, and I’m really sorry to say that one gender’s gonna be upset by what she discovered. There’s a, a gender element to their work. They also found that a test for autism was very effective at predicting collaboration and problem solving.

And that’s a test you can do. So you can Google Reading the Mind in the Eyes test. That’s the name of it, not the most catchy thing. I also tweeted it on a eat, sleep, work, repeat Twitter handle Last week, I should warn you that you can only really do the test once it repeats itself, so. It takes about 10 minutes.

I know those, those things where people say it takes 10 minutes, normally take about three. This takes a full 10 minutes. Gets quite exhausting in the middle ’cause you’ve been asked to judge emotions from 37 sets of eyes. But I should warn you, everyone at my work who’d. Did it too quickly, got very upset with the score.

So take your time. You can’t retake it, but I think you’ll find that fascinating. Now, no one listens to the end of the podcast. So let me say two things now. Firstly, slide down the page in the Apple Podcast app and give me five stars that basically helps my ranking in the Apple, uh, podcast chart. So that’s another nice bit of car man.

We’re starting the year off on a good foot here. Secondly, next week’s show is Daniel Coyle. And he’s got a new book out called The Culture Code, which is absolutely outstanding and we’re planning to bring him to London. If you’ve got a venue that can host about a hundred people do tell us, uh, because we’re looking to bring him to London in March.

Before that, here’s Anita Williams Woolley.

Thank you so much for joining me. I’m thrilled because I’ve spent the, the weekend consuming your work in collective intelligence. To kick us off, I wonder if you could explain the principle of collective intelligence.

Anita Williams Woolley: Sure. Yeah. So when we started this work, uh, the existing research that looked at intelligence in teams would focus primarily on the skills of individuals and the intelligence of individuals.

But we knew from our research as well as just our practical experience, that there are some teams that just have a better collective capability than others. They just work together better. Uh, and so we were really looking for a way to capture that. If there’s something that’s. Independent say, of individual intelligence or at least adding onto, uh, the benefits of individual intelligence that really is present in the connections among the team members.

So we started by drawing on traditional approaches to measuring intelligence and individuals, but devised, uh, a series of tasks. Aimed at gauging how well a group of people is working together. We sampled tasks that required them to collaborate in different ways. So to engage in say, divergent and creative thinking, to engage in more convergent uh, decision making, where they’d need to use expertise that different members might have.

Uh, somewhere maybe instead of making a decision, they’re just trying to execute a task really quickly and accurately. A variety of ways that. The existing research on teams has identified, you know, require teams to work together in different ways. And so we thought a collectively intelligent team should be able to do all of these things.

So in our initial studies, uh, we were just really testing the hypothesis as to whether or not there’s this collective intelligence. Are there’s some teams that systematically work better together than others across. Different kinds of tasks. And, uh, if we could measure that, could we also predict how those same teams are gonna perform in the future?

And so our initial study that came out in 2010 did provide support for this notion of a collective intelligence that was measurable and predictive of future performance.

Bruce Daisley: So you went on to look at the factors that then created that collective intelligence. Is that right?

Anita Williams Woolley: That’s correct. So we were curious, okay, if it’s not really primarily driven by individual iq, what are the other things that might be driving this?

And so we looked at a variety of things both about the people in the teams as well as the team itself. Um, so I can go on to describe those if you like. Yeah,

Bruce Daisley: yeah. Yes, please. First it’s calling out the thing that you pass over there, the idea that just having one brainy person in a team actually had no correlation to whether the team were more effective at dealing with these challenges.

Anita Williams Woolley: Right. So in, in one of our studies there was, there was no correlation and the other, it was just very weak. It was a lot weaker than actually we expected, uh, given the, the research to that point. Uh, so the things that we found that were actually more influential were things. Well, the first observation was that the proportion of women in the team, uh, seemed to be predictive of collective intelligence.

But in exploring that further, it really seemed that that was explained by another characteristic. Uh, we’ve come to call social perceptiveness, or the ability to pick up on subtle non-verbal cues and draw inferences about what others are thinking or feeling. Uh, so it turns out women on average have higher scores on this attribute than men.

So in essence, when you have more women in the team, you’re raising the average on that. So that’s something that we have continued to find across our studies, both in teams working face-to-face, and interestingly even in teams working together online, where even when they’re only. Collaborating via text chat and may not even know if the other participants are male or female.

So that’s been very interesting to us that this seems to translate, um, across, uh, those kinds of contexts.

Bruce Daisley: I just wanted to call out one thing there as well. You, you looked at the gender bias, it seemed that 50 50 teams tended to perform about average, and it was only when the majority of the team were female or it’s predominantly female, that you saw performance pushing ahead to the average.

That’s right. Isn’t it?

Anita Williams Woolley: Yeah, and we’ve um, we’ve explored our data a little bit more and continued to kind of look at this, you know, as to why that occurs. Uh, there’s a, a general finding in the literature on team collaboration that, you know, tends to observe that women, when they’re in the minority in a team also tend not to talk very much.

And it’s only when, when women are in the majority. That most of the women tend to contribute a lot more, but the men continue to contribute a lot too, even though they’re no longer in the majority. And so you have the highest levels of participation when you have teams that are gender diverse with a tilt toward having more women.

Bruce Daisley: And these were a vast range of challenges, weren’t they there? There was negotiation problems, there were mathematical puzzles. Can you give a snapshot of the range of challenges, please? This wasn’t just one or two sorts of problems, was it?

Anita Williams Woolley: No, although they are very, again, modeling after individual intelligence research, we kinda kept the problems a bit abstract because really what we were trying to do was rather than test actual knowledge, test the way that the group had to work together.

And we also tried to sample from both verbal and nonverbal kinds of tasks. So we had a, a range of verbal tasks, things. So some of the decision making tasks were things like uns, scrambling, uh, words. You know, and other kinds of word problems. We had brainstorming tasks that were more, uh, some were more word based, some were more picture based.

We had numeric puzzle solving problems like Sudoku. We had matrix reasoning problems, which were also kind of more puzzle based decision making. We had a. In the original study, we had a moral reasoning problem as well as another problem that was more of a negotiations problem called the the shopping trip task, where they had to negotiate over a limited resource, such as a car to go to go grocery shopping.

And then we had what we think of as execution problems again, where they’re trying to be very accurate and detail-oriented and fast. And so the one we came up with actually was the typing task, where they’re retyping together, provided text into a shared online document where they’re penalized heavily for missing words, for making mistakes, uh, et cetera.

So they have to carefully coordinate who’s typing what and not leave gaps, and not leave typos and things like that. That’s kind of a overview of, of the kinds of things, and over time in the years ensuing years, it’s been an ongoing process of coming up with new. Problems that we can use to really force teams to work together in different ways, problems that members can understand pretty readily.

So that what we’re getting is not just which team is less confused, but you know, which team is actually working together better. And kind of again, crossing the array of, of different kinds of tasks and, and verbal versus nonverbal domains.

Bruce Daisley: The other thing I was interested in, you appear to have said that there’s no advantage to having an evident leader in a group, having leaders in groups didn’t appear to, to make the team come up with better solutions.

Anita Williams Woolley: Yeah, and that’s something we’ve also continued to explore. So this was in our initial, um, studies, just looking at a leadership emergence, you know, natural leadership, emergence. We have another study that we’re, you know, preparing to put under review now, where we had in some cases. Teams appoint a leader.

So they, they kind of had a warmup task they did together to get to know each other, and then they voted for a leader. And in the teams where we had them do that, and we didn’t do anything to try to threaten that hierarchy by, for example, saying, okay, this is your leader for now, but later you could choose a different leader, which created an unstable hierarchy.

What we found in the teams that. Had a stable hierarchy was that they actually did perform better. So kind of being explicit in appointing a leader and a leader that is going to stay, had an advantage, having a leader, but then creating maybe a little competition where somebody could unseat that person later.

Reduced collective intelligence.

Bruce Daisley: So the social skills. Then you mentioned that women are better at these social skills. I mean, would you permit me to call them empathy? It’s the ability to read other people’s emotions and feelings. One of the things you used to measure that was this test that’s often used to diagnose autism,

Anita Williams Woolley: right?

That’s correct, yeah.

Bruce Daisley: Everyone in my work did it yesterday. Actually. It needs to catch your name, but it’s, it’s called the Reading the Mind in the ICE test.

Anita Williams Woolley: Yes.

Bruce Daisley: And you found that people who were good at these tests were better contributors to collective intelligence. Can you just talk through how that is and why, why you think that is?

Anita Williams Woolley: Yeah, no, we were against. We’ve been surprised by how consistently that’s been a predictor. As you mentioned, this is a test that was devised by actually a researcher in the uk, Simon Barron Cohen, and his colleagues to screen people for autism. It’s something that comes out of the tradition in cognitive psychology of work on.

The idea of theory of mind or the general ability to understand somebody else’s perspective, uh, to maybe anticipate how they’re gonna react to something, to understand how they’re thinking or feeling based on, on subtle cues. So this is one test. There are others that tap into this, this general ability, but what we find in groups is that when you have people who are higher on average on this, you also have some better collaboration behaviors.

Such as a, another thing we find consistently has to do with the amount of communication, but also the distribution of communication. Teams that have a more equal distribution of communication tend to have higher collective intelligence, because you’re hearing from everybody, you’re getting information and input and effort, you know, from everybody if they’re all contributing.

And when teams members are higher, on average, on the reading, the mind and the ice. Test. They also tend to have greater equality of communication, and we believe this is the case because those folks are better at monitoring when say they’re dominating the conversation and maybe scaling back a little bit and letting others into the, into the mix or inviting others into the mix that has these benefits for, um, picking up on, on things that might be going on in the team, inviting others in, managing the collaboration more effectively.

Bruce Daisley: Tell me this, you’ve observed that when people in a group read each other better, the team operates better, more effectively. A couple of questions come from that. Do you believe that this is a skill that you can teach? Can you, can you learn this?

Anita Williams Woolley: I think that’s a great question and one that several people, including some of my collaborators are, are working on because the data on this are met.

So there have been a few studies in the literature that have looked specifically at, uh, what kinds of things can you do to improve people’s scores on tests like reading the Mind and the Eyes? Um, there was one by some researchers, kit Castano a few years ago in science. Showing that people could do a, a literature reading intervention and it would improve their scores on tests like these.

However, some other researchers came along after and, you know, questioned, uh, how, how reliable those findings were. So the data are, are out on that. There’s another line of related research on micro expression readings. So a researcher, Paul Eckman and, and his colleagues have looked at, can you teach people?

Specifically how to read these, what they call microexpressions because these things are manifest in sort of how you crinkle your, the skin around your eyes or your forehead or your eyebrows or you know, various other muscles that you might move in your face. They do find that if they train people and there’s an online training people can take on this, they can improve their scores in reading a bunch of expressions.

We’ve tried it however wi in our studies and it does not seem to improve collective intelligence, so it does not seem to generalize. To this greater underlying ability that is speculated about in the theory of mind literature around drawing deeper inferences and maybe using those as indicators for things you should do to facilitate the work of a group.

So it’s, I think it’s an interesting and important question and the data are still, you know, not in yet fully on that.

Bruce Daisley: The best performing person in my office yesterday was my Irish colleague, niv, had interesting. And she said, Irish people are better at reading people’s eyes. Have you seen any difference between different groups of people?

Anita Williams Woolley: Um, well, what’s interesting is, so I haven’t looked at Irish people in particular, so that’s, that’s a very interesting observation. It would be good to look into that more. There are, there are some work in social psychology from the seventies and 80. Looking at a general ability of people who are in a lower power position that, and sometimes it’s, you know, almost evolutionary kinds of arguments that are made for why they would develop better skills at picking up on cues, especially cues that are given off by people who would have power over them.

Right? So to the degree that Irish people. Been oppressed. You know, it could be that over time there’s been a survival advantage to those who are better at picking up on those things. And so perhaps, you know, that’s, that’s kind of evolved in their culture. But honestly, I haven’t looked at the question myself.

So

Bruce Daisley: here’s an extension of an argument then. So, so if you are effectively saying that the thing that leads to the best problem solving in a group, the best actions of a group are the ability to read each other. And if you, if you will, permit me to call that empathy, they’ve say, if you’ve got these two office scenarios.

One where everyone sits with headphones. Uh, headphones aren’t typing at their computers, and another where people are talking face-to-face, sort of reading each other’s emotions, interacting with each other. Based on your research. Would you say then that it’s fair to infer that the computer-based team would be less creative, productive, capable than the team that are interacting with each other?

Anita Williams Woolley: So actually I would say, uh, it’s, it’s a little hard to say based on the description because it depends on if that, in either case, if that is how the group always interacts. So, um, what we know in, in the team’s research, and the reason why we very deliberately chose different kinds of tasks for the teams to do in measuring collective intelligence is that there are some modes of.

Working that are really well suited for certain tasks and more so than others. And so actually the collectively intelligent team would be really good at dividing and conquering when that is what’s necessary. So say we’re working on different parts of the code for, you know, a broader software program.

So we’ve had our face-to-face chat where we have figured out what we need to do and we’re all clear on the overall goal, and now we’re dividing up and we’re doing our work independently. I think it’s, what’s a problem is when a team is. Stuck in either mode, you know, either always together or always dividing and conquering.

And so, I don’t know if it’s true where you are, but in the US there’s been this affinity for these open office concepts where they get rid of everybody’s walls and they make everyone look at each other while they’re, while they’re working. And often students ask me, okay, so is that better for collective intelligence?

And I say, well. No, if it prevents the team from being able to adopt the mode of working that is best suited to the work that they’re doing at the moment. And so, you know, the ideal would be to have some flexibility, you know, in the space that you have so you can do the quiet work, uh, when you need to. Um, so.

Yeah,

Bruce Daisley: so, got it. So you are saying it that for moments of deep work where our individual intelligence or the application of what we’ve collectively decided upon is being played out. Deep work concentration are important there, but when we’re trying to be more than the sum of our parts to create, collaborate together in those cases face to face interaction and empathy to see, seem to have their real value.

Anita Williams Woolley: Yes. No, I, and I would say, right, and I think one fosters the other. Again, I think when you have people in the team who you know are very adept at collaborating, they’re probably also better at picking up on, okay, now we’ve kind of exhausted what we can do in this conversation. We’re not gonna be one of these teams that sits around a table and composes sentences together, because that’s a really unproductive use of.

Uh, you know, uh, you know, people’s face-to-face time. Now it’s time to divide up and, you know, work together more, more efficiently, more productively.

Bruce Daisley: I’m so fascinated with all of your work. What have you gone on to explore next? What questions have these discoveries opened up? Where do you think you’ll take it?

Anita Williams Woolley: Oh, there’s a lot of different directions that we’re working on, so we continue to work on refining our measure of collective intelligence. It’s that, I think that’s the kind of thing that you just work on until you die, because there’s always ways that you can improve it. You know, better ways to capture something, sample something, et.

So that’s why we, you know, every intelligence test has had many, many, many iterations. And so ours will as well in terms of, you know, new frontiers depending on, on which article you read about the robots coming. Some people have a rosy view of what this is gonna do for organizations when we have more artificial intelligence and some people have more of a, a dark view.

Um, we’re, we’re trying to cultivate the rosy view in the sense. That technology and artificial intelligence have the potential of helping teams in a variety of ways. So there are certainly technologies that can enhance the quality of what individuals are doing by say, making their work more efficient, making them more accurate at certain things, you know, whatever, um, the case might be.

But there are also some really exciting technologies for thinking about how to coordinate the inputs of members. So to make that aspect of teamwork more efficient. So we are looking, we’re, we’re conducting, just starting to conduct a variety of studies, looking at using technology to coordinate teams in a variety of ways as they work through the problems in our collective intelligence battery to both understand when humans are likely to be more receptive.

Of a robotic facilitator, if you will, um, as well as, you know, when those inputs will indeed enhance the quality of the coordination, collaboration that occurs. So that’s, that’s what we’ve been, um, starting to work on. It’s a, it’s a really big multifaceted problem. So I think that’s gonna, we’re gonna be chewing on that one for a while, but it’s one we’re really excited about.

Bruce Daisley: I’m so thrilled to attract to you the, the gender parts of your work I think will surely help us rethink how we build teams. I really look forward to seeing where you take it next. Thank you so much.

Anita Williams Woolley: Well, thanks for reaching out and I, I enjoyed our conversation. Thanks.

Bruce Daisley: Right. That was sensational. I do recommend you watch Anita’s Ted Talks, and again, I tweeted a couple of those out last week. Very keen to hear your opinions. Do give us five stars on the Apple Podcast store. Next week’s, Daniel Coyle. See you next time.