“Men have no friends and women bear the burden”

Lots of my favourite podcasts have gone on summer break, so I wanted to keep putting some episodes out.

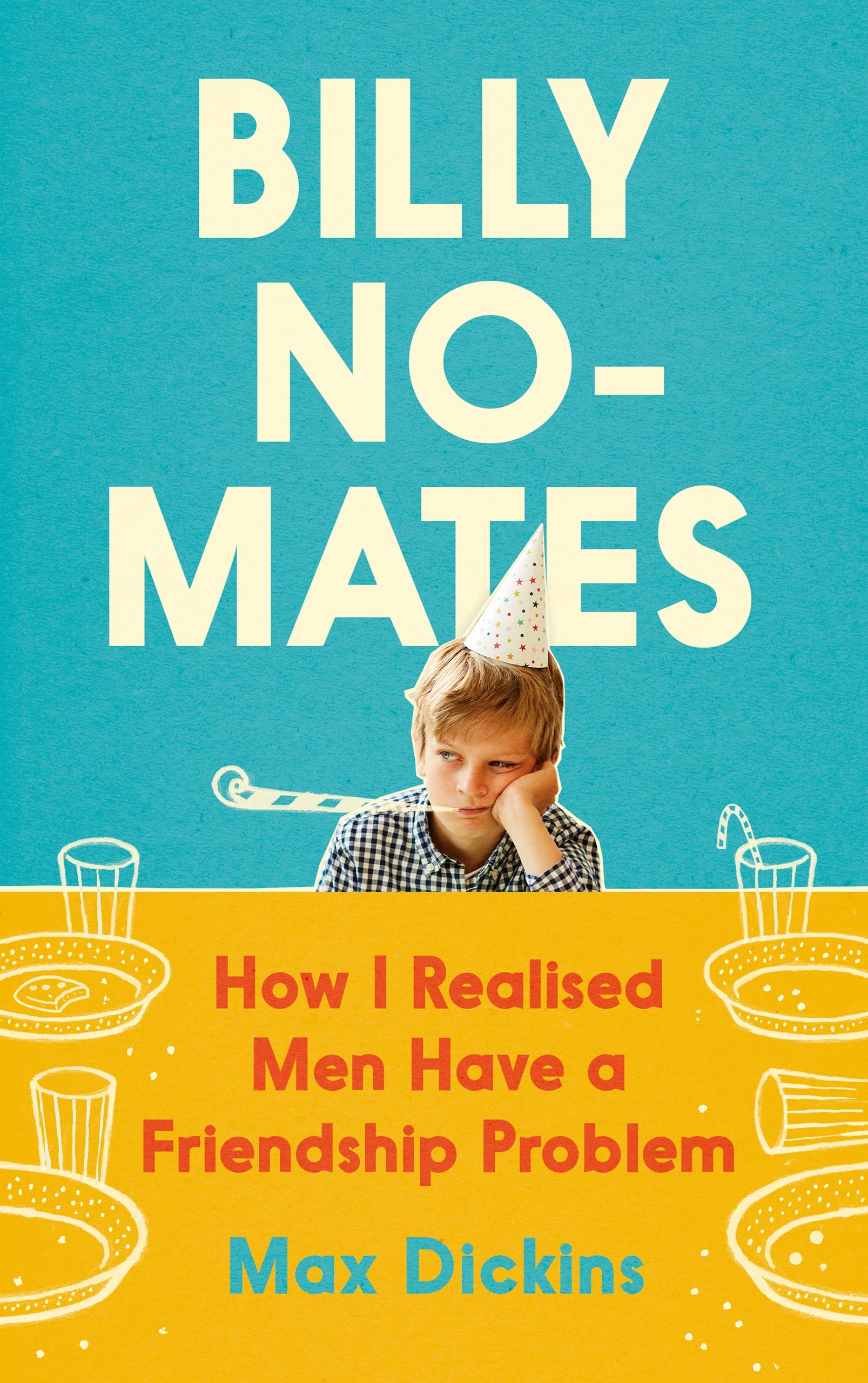

But maybe you don’t want something that is too work related in the midst of the summer, so this is an episode that is more psychology and life than workplace culture. It’s a lovely discussion with Max Dickins author of ‘Billy No Mates’.

I got so much from the book – and from the discussion. Max reflects on the geezerish persona he adopts with workmen in his house and wonders if it’s a performance and if it is a performance is it by him, or the workman or both of them. He considers how for many men adult life becomes a process of refusing to demonstrate – and then refusing to experience – joy. As someone asked of him, ‘what happened to these men’?

The article that the episode is titled after is here – we discuss it in the show: “Men have no friends and women carry the burden”

Roboty transcript

Bruce Daisley: Hello, this is Eat, sleep work repeat. It’s a podcast about work, psychology, and life. Been an interesting time in my podcast feed at the moment. Obviously, a lot of podcasters have gone away on holiday or something and I’ve noticed there’s not a lot of things been dropping. Rather than hanging onto some of these discussions until.

we’re back to school, till we’ve normal live resumes. I thought I’m going to share a couple of things as they happen, and this is a fabulous example because it’s a really good discussion that sort of transcends work really and goes into something more substantial in our real lives. If you accept that.

Distinction and it’s a discussion with max Dickens, who’s written a book that you’ve probably seen. I’ve seen it in a few places. It’s become a cultural idea to some extent, and it’s this book, Billy No Mates. It’s been serialized in the Daily Mail. There’s been articles in, I think this Sunday Times in The Observer, and it’s really.

A book that confronts something that you might be aware of that men, certainly men after a certain age, don’t really have friends. The way that one commentator that’s quoted by Max in the book says it is they titled a piece, men have No Friends and women bear the Burden. And that’s why I think this discussion might be really helpful.

’cause even if you are not a man, if you’ve got a man in your life, a brother, a partner, a housemate. Then it’s an interesting one to share with them about the role that friendship plays in men’s life and how we might think about it in a different way. One of the things that Max said to me just as the microphone went off it’s really frustrating, you have this conversation with someone talking through, tearing through this research and this.

This thought that they’ve seeded and then you stop recording and sometimes people say just these exquisite, brilliant things. It’s oh man, shall I ask him to do that again? But I didn’t ask him to do it again, but he said something really interesting. A friend of his said to him, my best friend.

I’m not sure that I’m his best friend and that uncertainty, that doubt about our relationships, he’s such a toxic force. It that anxiety about emotional. Revealing and knowing where we stand with people often is an inhibiting factor. There’s one maxim that Max leaves us with, which is a sort of an idea that I think we can all adopt and it’s a very stealable idea.

So a lovely discussion. I think you’re gonna really enjoy this ’cause I think this is a call to arms to try to. Embolden and strengthen our friendships and recognize how important they are in our lives. This is my discussion with the author of Billy No Mates, max Dickens.

Max, thank you so much for chatting to me. I wonder if you could kick off by just explaining who you are and

Max Dickins: what you do. My name’s Max Dickens. I am a writer formerly a radio presenter, and also I used to be on the standup comedy circuit. So I write books. I also write plays. So I’m joining you Bruce, at the moment from the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

I’ve got a show opening on Thursday this week. And. Also just the author of a book called Billy No Mates, how I realize Men Have a Friendship Problem. It’s really interesting because the story,

Bruce Daisley: the book really is this really rich and very enjoyable caper into, your own friendship and the absence of your own friendship.

In fact, you give a quote of an article here that was potent that I scribbled it down, which was an article that had gone viral at one point, which was men have no friends and women Bear the Burden. And it like, a series of things in your book. It forced me to reflect on my own life and reflect on other people’s life that I know.

So I’d love to just take a step back and hear. The origin story of how you found yourself writing a book like this.

Max Dickins: So the book arose out of a genuine necessity and a genuine challenge I faced in my personal life. I was intending on proposing to my girlfriend Naomi. I was literally in a shop in hat and garden at a jewelers with a female pal looking for a ring.

And we went to the pub afterwards and this female pal said so. We’ve got the ring. Who are you thinking of as Best Man? And my mind went completely blank and I just assumed I was, blanking. ’cause I was a bit overwhelmed. So I went back that night, got a piece of paper out and a pen, and I made a list of candidates who were my good male friends.

And I looked at the list. Most of them I worked with. And they’d think it’d be a bit weird if I asked ’em to fill that role. And the rest of them, I thought, gosh, I haven’t spoken to some of these guys for two, three years. And I suddenly thought, oh my goodness, where have all my friends gone? And then I Googled it, getting married, no Best man.

And there was something crazy, like 934 million results. Click on them. Loads of these. Guys are posting in wedding website forums emitting, they haven’t got a best man. They dunno what to do about it. And it turned out that actually male loneliness or a lack of male friendship is a real problem. And I thought I’m gonna solve the problem.

And by doing that. Find the best man. Look,

Bruce Daisley: the book is a very funny, and I can understand. You’re a sort of former standup comedian, and I guess you’ve worked in various different parts of comedy if you’re up there in Edinburgh, and the book is a very entertaining read. But it also through that, I think whether the people listening to this are men themselves or they’ve got men in their lives.

Actually, it invites you to reflect on certain things that have. Attributed to that loneliness and firstly ask yourself to appraise it yourself, because this appears to be something that men, they’re on a sort of tapering scale that they lose friendships. Is that right?

Max Dickins: Yeah, absolutely. So men’s friendship problem can essentially be seen in two ways.

The first one is that men tend to have some mates, so mates from the pub, mates from work mates they play football with, they often lack. What you might call close friends, intimacy in those friendships. So a recent study by Vember, for example, the male mental health charity, revealed that one in three men say they’ve got no close friends, and they asked that same group of men.

How many of your friends could you talk about something important such as a relationship problem, a health problem, a money problem with? And one in two men said they could think of no one at all. So that lack of outlook for that sort of friendship. And then secondly, what sociologists call network shrinkage.

So if you look at all of us, our social network tends to get smaller as we get older, particularly around turning 30, a late twenties of the summit of your social life. It shows out. But men’s social world shrinks a lot more. Than women. So the kind of question you look at then is what’s going on for these two things?

And there’s kind of two main theories really, and potentially a third one we might get at. And they all interact. In terms of the theories, would you like me to get into that? Let’s do it. Let’s do it. The first one is to do with what you might call gender norms. So masculinity.

Which is the unspoken rules that maybe men bring to their relationships including their friendships. When I reflected on myself, I didn’t think this was me. I didn’t think I was that archetypically, masculine or brought any of these. Inhibitions. But then I went to a party and I remember my girlfriend said, do you realize what you like with other men?

Do you see what you become? You become something completely different. Yeah. The bit of this that really

Bruce Daisley: struck me, it was that you played type side by side, how you interact with work men who come to your house. This adopting this sort of geezer persona. It’s something that I can certainly recognize as well.

Yeah,

Max Dickins: absolutely. So what I discovered is that I perform in a certain way when I’m around men and especially around archetypically masculine men. So that, the builder we had coming around to our house, I was desperate for this guy to like me and I would, pretend to be obsessed with football.

I’d I’d he’d talk to me about his car and I go, that’s very interesting. I, let’s see some phone, some photos on your phone. He’d say some pretty. Pretty backward things about women and I just leave it unchallenged. Just make those sort of vague noises that you do in the back of Ubers when the drivers say something that you don’t really want to get involved with.

But then he’d go to my wife and have all sorts of amazing conversations about his kids, about recommending sort of tiles huge aesthetic taste. And I realized that he was performing to me, I was performing to him, and like our masculinity was between us. And this is getting too. This idea of what it is to perform your masculinity.

We become. Different sorts of people. So in friendships, what did this look like? We tend to not wanna show affection in our friendships. So I realized the only time I’d ever told a guy in my life that I so much as liked them was after six or seven pints. Men don’t like to be the one doing the chasing or the organizing.

We don’t like to look needy. So we look at the other person in that relationship, wait for them to do it, but they often they won’t. And then the big one I looked at was banter. So the, one of the rules of male friendship, and I think a rule that membrane a lost. To their relationships is it should be light, it should be fun, it should be funny.

This sort of jazz of casual brutality we bring to it. So these are just some of the rules we bring. So to tie it together, these are things that get in the way of the more intimate conversations. You put a moat up around you through this performance. You can’t quite get at them. They can’t quite get at you.

So you have this sense that maybe it’s fun. But you don’t quite connect on that real personal level. It’s really interesting, isn’t

Bruce Daisley: it, because you force me to reflect on that. I, like a lot of people might say to yourself, I’ve got a sort of humorous aspect on life, or I try not to get too bogged down in seriousness.

And I guess, I saw that as a sliding scale with solemnity on one side and, the ability to see the sort of the trivialities of life on the other end. And so it was like placing yourself very much at the side where you just say we’re, look, we’re all just in these brief interludes on earth.

And so this is all incredibly trivi trivial. Almost every chapter I went through in the book, I was like. That’s really made me rethink this version of myself that I think I’ve constructed where I think, I’ve got the answers right. And actually it’s made me think this constant desire to try and find humor in things or to try and show that nothing matters to me is really flawed.

And forgive me, making it subjective here, go on, talk me through how. The research you’ve done on this has helped you understand it better.

Max Dickins: I was the same as you really, I think, and I just thought, wasn’t, isn’t, wasn’t this a positive thing? Wasn’t this a strength of mine?

I can really connect and relate to people with humor. That should be a great thing. It’s one of the things that I love about being friends with men, is that kind of that, that vibe. That you have. And it wasn’t so much research that led me to the conclusion I needed to change here was I actually through the pandemic, I had some time and I was being told by all these psychologists I was speaking to.

The thing is about men is, they don’t develop the language of intimacy, the vab, the vocabulary of it, or. The ability or permission to have these more intimate conversations. So I started going to a therapist to try and practice really, and it wasn’t for any sort of big personal reason.

And then after four months she said, the thing is with you, max, is you can talk about things in, in an intellectual way. You can talk about them in a funny way, but the reason why people don’t wanna reveal stuff to you is ’cause they don’t think you can reciprocate. And she said, so maybe that’s why you haven’t got any close friends.

And it was a bit of a haymaker. ’cause I sent myself tumbling back through my life and I realized, yeah, that’s what I do when I talk about stuff. I would get different sorts of hiding of ossification. One would be intellectualizing and one would be humor. Both of them in independently great ways of being in the world and sharing with others.

But I had no other gears on the gear stick and. It was that realization fed back and reflected back to me by someone who watched me relate for, up close for all these months. That made me realize that’s what I needed to develop. I needed to get the other, fourth and fifth gears.

Can I go there? Can I do the vulnerability stuff with other guys? Because someone says to you

Bruce Daisley: at one point that we’ve got this ability to reveal ourselves to others, and something got in the way. Something came and I wondered through that, whether these generational element of this, that, would younger people who appear to be more attuned to their emotion. For example you mentioned being uncomfortable with hugging friends, I think if you witness Gen Z kids and young kids now, yeah. They love it. They love embracing their friends and so the thing that’s got in the way for you and a generation of people like you do you think we might be heading into a more emotionally empathetic time?

Max Dickins: So that’s, this is a really interesting question, I think, and you are right, these sort of norms are softening. I spoke to a guy called Fernanda Deusche, who runs a marketing agency called New Macho, and their kind of gig is to try and make marketing and advertising more inclusive. So you see different versions of men compared to the sort of men that I used to see on tv.

The classic example is the links campaign spray more, get more. That sort of quite, exaggeratedly masculine way of being a guy, and they did loads of research and they said a lot of the norms that I’ve been discussing, people do still believe in actually. These younger generations are a mixture of very modern ways of being guys, certainly in their attitudes to sexuality, to women.

To physical intimacy as you’ve said, but they also have some of the more old fashioned views that I’ve discussed. But you mentioned the research there. So I spoke to a psychologist called Nibi Way who is from NYU. She’s, she spent her career studying boys friendships and also men’s friendships.

And what if you look at the research up about to the age of four or five, if you see boys and girls being together. Or being friends with one another. They are as equally emotive as each other physically, and also in terms of how they express verbally their emotions. And then there’s an arc of disconnection near Bway says, and it peaks or starts to become most profound when puberty hits.

And the girls start looking more like women. And the boys start looking more like boys and suddenly boys then start, being less willing to admit they want these friendships. And when she interviewed these boys, 14, 15, 16, they would start associating friendship with a sexuality gay, with a gender female, and with an age young.

And I thought that was really interesting. Then the question is, I think, these sorts of thoughts, is it to do with culture? How we are socialized brought up, or is it something a bit more innate? Now, that’s not very a trendy way of thinking at the moment, but you talked about the changing generations there.

Clearly culture plays a big part and these things are softening. But I do wonder if not only are these cultural ideas more sticky than we think, but also there may be something a bit more innate at play here.

Bruce Daisley: One of the things that you present is the idea that certainly as men go through their lives, they encounter.

A scarcity of joy. They, it’s not only the friendships that go but a sort of, yeah, a playful frivolity. And and it’s really interesting as a result of that, one of my own frustrations to, to echo some of what you said is during the pandemic when we were in this forced isolation, I was incredibly frustrated when some friend friends didn’t interact on WhatsApp groups.

And then, so when I would message them individually, they didn’t even respond to that in a sort of, in a playful call and response attempt to just try and have dialogue about that day’s daily briefing or, like just to comment on the world around us. And it just struck me that idea that a lot of men see the sort of, the absence of joy a real.

Dearth of joy in their lives. That struck me as a really big idea.

Max Dickins: Yeah, I’m really glad you’ve asked me this. ‘Cause I think this was one of the most profound things I learned as well. So I spoke to a psychologist in, in, in the states called Ryan Kelley, who’s done a lot of. Ted talks around masculinity.

He also works as a therapist specializing in working with men. So he knows his onions here and he said that a lot of men experience, and this is a direct quote, the death of joy. And why do they experience the death of joy? It’s because he’s saying that a lot of men, because we won’t express emotion or we are, we’re taught, socialized not to do that.

We slowly become detached from it ’cause we’ve repressed it from so long and we just don’t feel the amazing emotions of life. As thickly or as explicitly as as a lot often that women do. And he’d say he’d have men in his therapy office. He would say, I, I’d be with my wife or my child.

And, something would happen, maybe a balloon was brought into the room and you’d see them light up and they’d be laughing. They’d be going, wow. And these men would look at their wife or their kid and be like, oh my God, I wish I could do that. I wish I could feel like that. Which is, so grim.

But then if you think about it, friendship in a more sort of specific way. We often don’t like, I think as guys, and this is a generalization, talking about the great stuff, there’s a lot of talk about men not talking about the hard stuff about their life, but even celebrating the amazing things or talking about things you really want.

Often we won’t do that, and that’s so much part of what a great friendship is. It’s about not just commiseration, but celebration. And we’ve gotta be willing to let ourselves go there. Here’s an kind of a personal example from something else that’s happened to me. I went with a group of friends to see, a cricket match last summer, one of the games in the hundred. And on the way out we are just going through the gate and my friend Ollie was looking through his phone and he skipped past a photo of a finger with a ring on. I said whoa. What’s that? What’s that? He wasn’t even trying to show me it.

He said, oh yeah, I’ve got engaged to my girlfriend. So I was like what? We’ve been here for four hours and you’ve not mentioned it. I said, but that’s brilliant. I said, let’s go. Let’s go now and celebrate now. And I made him come with me and ha have a drink and really enjoy that moment.

But he, I don’t think. We had the way of exploring that or sitting in that, or he didn’t trust us to do it, but I just thought, wow, that’s not a bad thing. That’s a brilliant thing. And he, we were unwilling to do it, so Absolutely. It’s part of friendship.

Bruce Daisley: It’s really interesting. Along the way you encounter Robin Dunbar and you chat to Dunbar who’s transcended his immortality lives in the sense that he’s responsible for this number I’d love to hear.

Some of the evolutionary science to this. Yeah, absolutely.

Max Dickins: So I mentioned there were sort of two main theories. The first one is what we’ve explored, which is that we’re brought up to absorb these gender norms or what it means to be a man and it gets in the way of intimacy. So the second theory, and Dunbar is probably the leading proponent of this Dr.

Robin Dunbar’s evolutionary psychologist. And he came up with Dunbar’s number, which a lot of people would’ve heard. Which is essentially a version of the social brain hypothesis, which says is because of the size of our brain, there is a limited number of friendships or meaningful, stable relationships we can hold at any one time.

And that number is drum roll 150. But what is maybe more interesting about this is that 150 beneath it are a series of other numbers that suggest that our friendships or our key relationships happen in layers. So the first one is five, so that might be your spouse, couple of friends, maybe a sibling.

The next layer is 15, so another 10 people on top of that. Then 25, 50 up to 150 essentially. These expanding le levels of friendship have different levels of closeness. So that’s all good. Now, what’s interesting when it comes to men and friendship versus women as friendship is that Dunbar has done loads of research that suggests the male and female social world is.

Actually very different, and there’s quite a lot of evidence for this. So here’s a simple way of expressing the difference. Female friendships are often defined as being face to face based around talk a lot of emotional disclosure. Women will often have one defined best friend, often that they’re more intimate with than their spouse, which is not what you get with men.

Male friendships tend to be. Side by side based around sharing activities as in doing stuff together, often thriving in groups. So these are, they look very different. And then the theory goes that this is, comes from our deep, in our evolutionary past where men and women would rely on their friends for different things.

So for example, if you, and obviously we had different roles and these roles have changed, I should say. Women would require to have very close one-on-one friendships because if they were rearing children, if you were gonna leave your baby with someone to pop up the road to get some water, whatever it was, you’d have to really trust that person.

You have to really make sure they were gonna look after your baby. And they, that sense of closest was crucial. Whereas men would have to be hunting, they’d have to be often being the fighting cohort of groups, so they’d have to be able to. Form more casual group-based bond and form these more hierarchical groupings.

And so therefore, the theory goes social style, social preference. We don’t recognize that, deep evolutionary past anymore, but it’s still reflected in how men and women live and do friendships in the modern world.

Bruce Daisley: And so when you chatted to Robin Dunbar and you explained your situation to him, what did he advise you to do?

So

Max Dickins: Dunbar is a fantastic bloke and talks about this stuff in a very. Witty way. He laughed and said, I think you’ve got to think about what a close friendship is, a bit differently to maybe what you assume it is. So we mentioned that Vember study earlier, Bruce, and one of the key questions there was how many people could you have a conversation about health, worry, money, wire, worry, work, worry with.

He said maybe for men, intimacy or closeness looks a bit different, so you should stop obsessing over having better conversations and vulnerability and all that stuff and accept that. For men, close friendship might be much more an intimacy based in doing more of a covert intimacy. So his big advice was if you wanna maintain friendships, you gotta do stuff, is you gotta do the five side leagues.

You gotta get the guys together that used to be good mates with and climb the mountain every couple of months or or equivalent. His big one was join a club. He said that is the number one thing you could do, join a club. And so I did,

Bruce Daisley: I find this so intriguing, this idea that joining groups, joining clubs, it, it feels a bit too Boy Scouts.

It feels a bit too forced fun, doesn’t it, for a lot of us. But I love the variety of attempts that have been made, whether they’re men’s sheds, the attempt to try and create something that is gonna get past this cynicism barrier that a lot of men have got.

Max Dickins: Yeah, absolutely. So Men’s Sheds came out of Australia and it came from a very simple start where local governments in Australia were trying to solve male loneliness.

And so they do things like put coffee mornings on and they’d find that. Older women would show up, but men never would. And eventually, a slightly boardy Australian guy said, I’ll tell you what you wanna do, if you wanna get men to show up, is build a shed, give them some tools and let ’em get on with it.

And so they did. Men’s sheds were born and it is the most successful intervention. A male loneliness ever invented. I went to one in Teddington in West London, and it was just a shack with some tools in. And the Lances would show up at various ages and they’d make amend things, and the guy who ran it says through making amend, through, making amending things together, we make amend each other.

And I thought, what a brilliant definition of friendship. Which is famously hard to define. But what was interesting was most of the guys weren’t in the shed fixing the pepper grind or whatever one of them was doing. They were having a cup of tea and a chinwag. But what they needed was a pretense to get together.

You’ve gotta have a reason to be there, something to do, and then you can’t stop men talking. But I think what’s interesting about this is that it starts from the basis that men. Don’t necessarily have something wrong with them, you’ve just gotta design a context where their socializing will happen, which is a slightly different approach from the psych psychological approach, which is men need to learn all these new skills.

There’s probably truth in both, but that one with sheds, which we’re exploring now, is maybe not one that is of the, now

Bruce Daisley: it’s got a real timeliness to all of this discussion because I guess the truth is that a lot of us now are finding ourselves working from home. So where we might have built some rapport, some.

Some humorous engagements with colleagues at work. Maybe a degree of self revelation, revealing ourselves to colleagues and chatting to them. Some of those casual conversations have gone now and a lot of us are living more isolated lives, and it begs it, it presents the potential that rather than this getting better, that actually we might look back even on this era with some degree of nostalgia, thinking at least there was some.

Connection there and a more isolated future. There’s something really interesting about the way that we have a relationship with work and people broadly are engaged with their jobs. If they say that they’ve got a best friend at work now that’s for men and women. But for people who work hybrid, the latest researcher came out a few weeks ago, said that about 17% of people who work hybrid report having a best friend at work.

So even, aside from your own proper BFFs set up, work. Was in some ways a proxy in some ways for this, and it found like it, it sounds like actually in your own experience, people that you worked with, were on your potential best man list so it could work as a proxy.

It potentially we could find ourselves seeing this get worse, I suspect.

Max Dickins: Yeah, I think it’s really interesting. So as I was writing this book. A lot of it was over the pandemic. And the pandemic is one of the biggest shifts in the social world in, in, in the history of man and womankind. So I think this could be a good thing or a bad thing.

So from the perspective of work, what’s great about work is it’s a, is it’s a structure where we can meet people and especially men, as I’ve said, rely on. Work more than women. So there’s a, an interesting thing that came out of my research was if you look at retirement, bereavement, divorce, men suffer worse mental and physical health outcomes than women after those, because they are more isolated.

Those structures are really important for men. So having less friendships to in the workplace. I would suggest it’s probably gonna be a bigger problem for men than it is for women because they’re more isolated generally. However, there’s also a big opportunity here in that if you are spending less time at work, maybe there’ll be a rise of localism and structures locally where you can make friends around there.

As an example, near where I live in Ton in Southwest London Now. I’ve joined this CrossFit gym, although you couldn’t tell from looking at me and I spoke to someone walking back from there the other day and they said, oh, I always wear the t-shirt for this CrossFit gym. Because around town people stop me and say, oh, you a member.

I’m a member too. You must come to the social. Now, the fact that they can go to the CrossFit at 5:00 PM or at lunchtime ’cause they, they are working from home is in a sense giving them another network. But. Losing that structure of work is putting all the impetus onto the individual to rebuild that, those social structures.

And that’s where I think it’s gonna be interesting to see what happens. Are we gonna be able to replace. The structure. ’cause as Dunbar said, the structure is probably the most important thing about social life, although we like to think it’s spontaneity structure is what keeps it going.

Bruce Daisley: Interesting. What in the sense that, if you’ve got some old college friends that you studied with 10, 15, 20 years ago. Actually, it’s the structure of having the discipline that we always meet up every November. It’s just having that. Yeah, absolutely.

Max Dickins: Yeah. Those closed loops, which is why, university and school especially a great ways of meeting people is ’cause you have that huge amount of time.

There’s some interesting research that’s come out about how long it takes to make a best friend and it’s research from people who’ve moved to new cities or. Gone to universities and it’s about 200 hours and that’s quite a long time. But what was it more interesting was it’s the intensity of this time not so spread out.

It’s the repeated interactions over a shorter period of time. So those places, which is why clubs are so good, which is why workplaces are often great if you can. Have the social side of work lead to friendships. So if you lose those self-fulfilling loops and you don’t replace them, you are then rely relying on the miracle of sinking diaries, of everything being front of mind of you having the energy, the time and the head space to organize your social world.

Whereas actually we used to. Have what’s known as third spaces, which is not work, which is not home places in between like a church, like a gym, like a coffee shop, where we would meet people and that I, a lot of the people who I spoke to who are looking at loneliness say. This is one of the major societal changes, which is a challenge.

And like you say, I dunno what’s gonna happen in the future. We might look back on this, even this era with nostalgia. The

Bruce Daisley: best thing about the book is that ’cause it’s so light, it’s so humorous. I would I don’t wanna say light in a pejorative way, it like incredibly readable. The, you could see a woman gifting it to her.

Partner saying, I’ve been reading a lot about this and this sounds like it might be the answer to your so I wonder if you could wrap it up with a bow for us in the sense. Without doing the Hollywood happy ever after. What have you changed as a result of thinking about this?

Max Dickins: Just to speak to about women giving it to their husbands.

Generally women are more interested than men in this book. I’m finding. Why do you think? I think because, hi, his, why men often treat the women in their lives as the HR department. And they often will outsource the social work to them. They’ll cuckold their social group because maybe theirs has become slightly withered or they don’t want to do the work of maintaining friendships.

And you mentioned the article, men have No Friends and it’s women that bear the brunt. This similar sort of ideas that men. Are much more reliant on their wives for the emotional support, but also literally to do the social stuff. A good example, I’ve written a whole book on this weekend.

Me and my wife hang out with two couples, both her connections predominantly. She organized it and it was great and I’ve got better. But think a lot of men see themselves in that pattern and a lot of women see their husbands. And I’m gonna connect it back to that point to answer your question properly now, which is, what have I done to change? There’s the three things predominantly. One is that building these rituals, these structures, these routines, these activities. So I’ve not joined a men’s shed, but what I have done is I’ve run a fortnightly five side league for friends, and I do all the organizing. I text everyone.

It’s not very glamorous. It’s not in a bow. It’s not the end of a Hollywood movie. But that structure, not that keeps us having a reason to meet up. We go to the pub afterwards. It’s keeping everything going. I also run a thing called pub club, which is a similar sort of thing. Once a month I rent a room out in a pub.

I text everyone and I say, come if you can, and text someone. You’ve been, you’ve said those immortal words of male friendship. We must have a pint sometime, right? And just show up for 1, 2, 3, 4, soft drink, beer, whatever you fancy. The second thing is I’ve got this phrase called Be the sheer. Connected, I think to the thing we’ve been talking about not relying on wives, girlfriends, female friends to do the social work.

I spoke to a male friend who’s Bri, who’s got great friendships and he says, my mates call me the Sherpa ’cause I organize everything. And they say to me, but if you didn’t organize it, we’d never do anything. We never see each other, so I thought be the sheer. And I’m always the one who goes first, who sends the texts who organizes the meetups.

And sometimes it’s hard, sometimes it’s easy, but that’s something I’m a lot better on. And then finally expand your toolbox. Have different ways of being with each other. So not just doing the banter stuff not also showing up and going first with the more vulnerable stuff. I’m much better now confessing when I’m having a bit of a tough time or ringing someone up with some great news ’cause I wanna share it.

And those sort of little acts of intimacy have made a massive difference. So three rules I had is show up when asked do I stop showing up? And that’s why a lot of the time my friends disappeared, go first when not, and keep going even when it’s hard. So those are the kind of nutshell things I think anyone can do.

It doesn’t have to be difficult, but you do have to do something.

Bruce Daisley: Firstly I would say it, it’s that degree of recognition. It’s that, re recognizing that you are in this zone where you’re seeing your friends less frequently. There’s just less fun in your life. You’re having less laughs than you, you have before.

And making a conscious decision. I love the be the Sherpa one though, because, sometimes I arrange some annual drinks every year for some colleagues that I worked with so long ago that I wouldn’t wanna put a number to it. And every year everyone says to me. Man, thanks for arranging this.

You wouldn’t believe how easy it is to arrange this. I literally get the email list from last year. I choose the day I’m gonna do it. I name the, it’s the easiest thing. The hardest part is writing two trivial, silly, ridiculous lines in the email saying this is where we’ll be. And every year. People say, thanks so much for doing it.

It’s it, this couldn’t be easier. Yeah. This couldn’t be easier.

Max Dickins: It’s so funny, like when I do the five side thing, I always feel the same. I get the same feedback going, oh, thanks so much mate. And then when we have a month off or something, because maybe like I’ve done a load of press for the book and I’ve had to, I haven’t been able to organize it.

I get all these texts going like, when are we doing football? When are we doing football? And I say to them, it’s lads. It’s not hard. Just email this email. But the pitch we already always play on. You’ve got the WhatsApp group, you’re done. It would take you literally, like you say, yeah, no time at all. But then some guys just are not very good.

Like I was. But the trouble is if the, everyone in the group has the attitude, nothing changes. So you’ve gotta be the one to be the sheer. And do you know what be the sheer, the thing that comes back to me on Twitter or on LinkedIn or on conversations when people said, oh, I enjoyed your book, is be the Sherpa, that one phrase.

And I think that’s great. I might have it put on a mug or something. Yeah, you should. I love it.

Bruce Daisley: I love it. Just a very simple call to arms for all of us to adopt. Fabulous. I’ve loved it. I read a lot of these books, and that was by far the most enjoyable of the year. Thank you. I love, I loved having the chance to chat to you.

Max Dickins: Oh I’ve always listened to this podcast, Bruce and I get your newsletter. So when I found out you were interested in having a chat, I was delighted. So thank you for having me.

Bruce Daisley: Thank you to Max be the sharper. We can all be the Sherpa. It’s amazing how easy it’s to be the Sherpa, and I think there’s an application for all of us in our jobs, but as well as in our home lives, be the person who organizes the fun stuff and having no embarrassment about embracing fun stuff, doing stuff.

I’ve really enjoyed that discussion. It made me reflect on my own life. I, like everything, we all think we’re better than average at everything. And I think I’m broadly better than average at that, but it made me think a lot about it. Reach out to a friend. Be the sharper, arrange something.

Thank you so much. I’ll see you.