Improving work with play

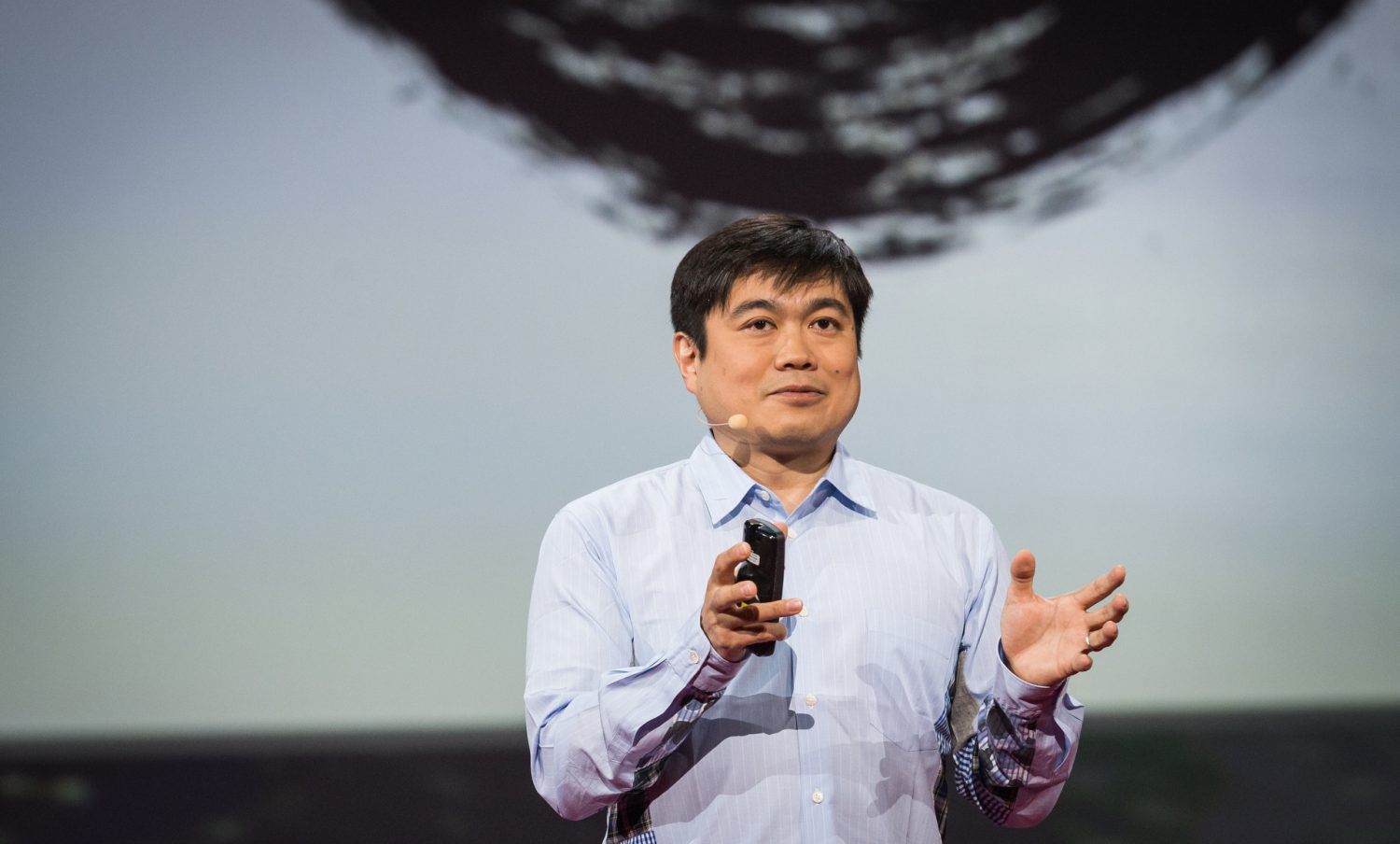

This week’s guest has an incredibly diverse backstory. Joi Ito runs the Media Lab at MIT.

In his new book Whiplash he gives an account of how the only way we can improve work is if we build cultures that are set to innovate and experiment.

This is a brilliant and fascinating insight into building creativity into our jobs.

Joi was taken around Shenzen by Bunnie Huang (Twitter, Wikipedia)

The conductive stickers that Joi talks about were created by Jhi Qi. More details here and here.

Transcript:

- “There’s a huge cost of permission” – we need to get to a position where, for everyone permission is presumed as the default

- Email is a flow problem. You need a method that prevents your demands growing every day

You talk about the change of how innovation is happening. The most vivid is the description about the Chinese mobile markets in Shenzen. These crazy pirate spaces where new phones are invented almost on the fly. For people who have never been there could you evoke the scene?

JOI ITO: So one of my favourite trips most recently was a trip that I made to Shenzen and I went with a couple of my students and one of my favourite researchers, Bunnie Huang and their provost. Shenzen is really one of those places that it’s very difficult to imagine. And you really have to be there so I’ll try to explain. But first of all that the image that people have of Chinese factories is a kind of a stereotyped image of a particular set of factories. The factories that our are students and we work with are a category of factories that most people don’t think of when they think of Chinese factories. So when you go the person who’s in charge of the factory lives in the factory. Everybody lives in the factory. At least all the people that we know there are happy they eat meals together. They sit around and have these wonderful conversations about manufacturing and design. One of the people that we worked with was this young woman who had eight months ago just been working in a textile factory. But was applying a lot of what she had learned into electronics. In these little small factories what you get is you get bits and pieces. A little bit of a Nintendo run here a little bit of an Apple run here.

So you think when you think of Chinese factories you might imagine these huge monolithic factories where you’ve got these robots just running this machine. But in fact what it is, is this amazing web of thousands of factories each with their particular talents and their particular skills. When you go in and you say I want to make a flexible printed circuit board. Have you ever done that? They’ll say no but we could maybe do this and my aunt over there has this process that can do that. My uncle over there might be able to help you with this. And before you know it by the end of the day you’ve invented a completely new manufacturing process to design something that’s never been designed before.

One of the things that we deployed from the Lab was circuit stickers that were designed by a young researcher at our lab named Jie Qi. And she wanted to create a way to stick circuits onto a note pad and then be able to draw lines with conductive ink and allow little girls or parents or whoever to be able to just draw and have circuits that worked. She needed these adhesive circuits stickers so she went to Shenzen – and in probably only in Shenzen could she have figured out not only how to produce these, but produce these at scale – so that you could get them out into the world at a low enough price so that thousands of people could use them. And then give her the kind of feedback on the research that she was interested in. So sitting on in these in these factories you’re you’re with these people who are bringing expertise both from other industries but also they’ve been sitting there making phones for every single phone manufacturer around. When our student says you ‘I wonder how you might do the surge protection in order to meet the safety guidelines for Western markets?’ Well they said ‘well there’s probably three or four ways to do it’. But because they’ve been watching how all of these other companies do it they’ll give our guys and girls advice on all this stuff. What’s fascinating is one: the extent of manufacturing knowledge that’s there on the factory floor. Two: the fact that these each of these factories is like a family with lots of people who hang around. Most of them (not all of them) but most of them enjoy their work. Most of them are saving up lots of money because they don’t have to buy clothes, they don’t have to buy food and they don’t buy cheap cellphones or buy original iPhones. The other interesting thing is, because everything is in proximity with everything else, they never say no. When you say ‘I need a cable that’s exactly this long with this connector and a flexible circuit board’, everybody’s like ‘OK let’s figure out how to do that’. Within walking distance you can often figure out how to do anything. So it’s this amazing place where manufacturing and innovation have come together. It really is a Silicon Valley for hardware. There’s obviously some parallels and some differences between hardware and software. In software Linux developers can be all over the world and can be working together on the Linux kernel. The difficulty with hardware as you kind of have to be there and face to face.

There’s a real value to the physical proximity of everybody being close together. In the West we had free and open source software in Shenzen there’s a different style, some people may just shake their finger at and say they are disrespectful of intellectual property. I will point out in fact that if you go all the way back to the early Silicon Valley when they were making computer chips a lot of the engineers did in fact (behind the scenes, across competitors) share a lot of information. For the development of really important ecosystems the fact that people in Silicon Valley can leave one company and go to another company is a really important way for knowledge to mix across companies – even though they have lawyers. In Shenzen what’s amazing is they have all of the manufacturing knowledge from all these different companies coming together. And so there’s that piece which is the ingenuity and the fact that the manufacturing engineers are all there.

The other thing that sort of blew my mind was Bunnie took us to the market where everything is on sale. And so when you go there, first of all lots of factories are in the business of making iPhones or parts for iPhones. So it makes sense that when you make a big printed circuit board and three out of the eight are bad. They throw them away.

Well somebody picks them up and cuts out the parts that work. All the way along the process of building a phone you have parts or sets of parts that don’t work. You go to this section of the market which is for iPhones and everything from the little button that you push to a nearly complete iPhone in every state of build between you can find iPhone pieces. On the street you find people with piles and piles of bricked iPhones flicking all the parts into little bins as they munch on a McDonald’s hamburger. Then they take these bins full of the chips that still work – because they test them all – and then they put them back onto these tapes. For printed circuit boards in these factories they use these machines that automatically put the components onto the PCBs. The way that they feed all of the components into these machines are these long tapes. You buy resistors and chips for these factories on these reels. But a lot of these reels are of literally little tiny parts that are flicked off of broken phones into little containers. Then somebody putting them back onto a tape. Then a factory saying ‘oh we’re out of part A, B and C’. They go to the market and they buy a bunch of these junk parts and stick them back into the phone. And so on the one hand you have all these broken phones and all these different things. And then I would bet that almost any phone that you have in your pocket actually has some recycled parts in it. It’s this amazing ecosystem. The funny thing is we were wandering around. There all these phones that are just built in there. Some of them are called Shanzhai phones or pirate phones. There’s one found that had this particular chip that was very rare. One of our companions said ‘they can’t use this chip, this chip is only licensed to be used in this particular phone’. So you know what they probably didn’t buy these chips illegally they probably found a bunch of broken phones, they got flicked out, they had the schematics and they built it into the thing. It’s a very different way of thinking about hardware when just about any part, and even the illegal schematics for all the phones that are being manufactured are available and people are able to hack these things together.

A lot of what you talk about leads into this culture of innovation, you talk about moving from push to pull. Can you talk through the shift of push to pull?

JOI ITO: I think that a lot of the principles in my book are all about the same thing. What happens when you are able to move things and information and connect the collaboration, the distribution and coordination all over the world at real time at nearly no cost you have the ability to harness the emergent nature of innovation of systems. In the old days when you weren’t connected you had to plan really far ahead.

You would say ‘I will meet you on the third moon of next winter at that inn at the top of the hill’. Once you’d decided that you couldn’t change your mind, that was when you were going to see that person next. But now when you log on and fire up your chat client or jump into the IRC channel or go into Facebook you can see everybody’s availability. You can say Hal is online, Mary is online. Maybe they’re the right people to to drag into this. There’s a little bit of randomness but in fact randomness is sort of the precursor to serendipity. Serendipity is tremendously interesting and valuable in a lot of ways. There was a great New York Times article a couple years ago that said that half of all inventions are by accident and it’s actually no accident. It turns out I think when you think about discovery or innovation as a result of a search. There’s the old saying everybody looks for their keys under the lamppost because that’s where the light is. When you think about disciplines or you think about markets or you think about a bunch of similar people trying to find a solution to a similar problem. They’re going to tend to look in the same place in the same way. And there’s a lot of low hanging fruit or whatever metaphor you want to use in those neglected spaces. And often those neglected spaces are just a glance to the side.

And so when we talk about focus and plans what it also means is that you’re sort of shutting down your peripheral vision and saying ‘No I just need to make sure I get to my goal. I don’t care whether they’re daisies by the road or whether I see my friend crossing the road over there’. You just need to get to where you’re going. And in many cases that’s important. When you’re rushing to the hospital or when you know exactly what you want to do and you only have a certain time execution and focus is very important. But when you’re exploring, what you’re thinking when you’re trying to be creative the ability to open up your peripheral vision is tremendously important. But also this idea of the power of ‘Pull’. So to bring it back to Shenzen, there may be dozens of ways to get to a particular end point but by brainstorming and running into each other and running around the market and looking at things you start to get so many different ideas on the paths to get there. And the other thing that’s really important is that you get the resources that are available now. Actually you can find a lot of this originates from the Just In Time manufacturing of the Japanese car companies back in the day. When they were trying to lower inventory by having things show up just when they needed them rather than stocking a whole bunch of inventory. Because the problem is if you stock a whole bunch of inventory and you decide that there’s a error or you want to change the model or you want to do something different, you can’t because you’ve got all this inventory.

If you’re pulling things just as you need them you don’t have that inventory risk. You’re able to be agile because you say ‘we’re going to change the design here, we can change this part here’. Or we just had a earthquake in Japan and this part is no longer available: how do we redesign the iPhone using parts that are available? And that kind of agility comes with this Pull over Push, this real time nature. For instance when we did this thing called Safecast which was a project that we started after the earthquake in Japan a number of us were concerned because the government and the power company weren’t giving us very good information about the radioactive cloud that was dispersing waste around Japan. A bunch of us got together and we found some people that were good at mapping. We found some people that understood high voltage electronics to make Geiger counters we found some people that knew a lot about Geiger counters. Within a month we were able to find a person doing the maps, a person who had worked on Three Mile Island’s monitoring system afterwards. And we were able to put together a group that could design a mobile Geiger counter put a Web site together, figure out how to do the measurements, get a bunch of volunteers in cars and drive all over Japan – over 60 million data points now. With almost no money, starting after the fact we were more successful than any NGO or any government. But it literally was going on to mailing lists and looking for these people who were available who happened to know exactly the right skills that we needed and then being able to coordinate with them at nearly no cost. So I guess the last thing I will say on this point is, a lot of assets on your balance sheet whether they’re lines of code or printing presses or patents are all assets but are liabilities for pivoting. So if you’ve ever been in a product meeting with engineers and you’ve done two weeks’ sprint and you roll out a new product and you say ‘that’s not working’. You know YouTube in 2005 was a dating site with video. Imagine that meeting what they’re seeing. The default was “I’m male between 18 and 35, upload video”. This isn’t working. All the engineers who’ve put blood and sweat into this don’t want to dump the code and pivot. But somehow you’ve got figure out what the next thing is. The longer you’ve spent building and planning and stocking, the lot less likely you are to be able to pivot. If you’re a big company who has a Vice President of video dating and you’ve you hired a thousand people and you patented a million things, you’re going to say ‘let’s try it a little bit longer’. Whereas if you’re a startup that’s only spent two weeks on it you can say you know ‘let’s try something else’, ‘let’s go jump on and become the video embeds for Myspace because the Google guys aren’t moving fast enough’.

So in a world where things are changing very quickly this lack of dependence on the inventory, this ability to pull the freshest people in the freshest idea when you need them. And then to be able to embrace serendipity rather than sticking to plan. I don’t want to diminish the need for focus and execution in some phases. But to be able to pull back and harness serendipity and speed is a tremendously important survival piece these days I think.

What I’m inspired by by MIT’s Media Lab is how you incorporate these things into your DNA. One of things you talk about is the difference between disobedience and criticism. One of your phrases is that you don’t win the Noble Prize for doing what you’re told – and you really try to bake these things into your culture. Could you talk about that?

JOI ITO: So the interesting thing about the Media Lab is that the Media Lab is 31 years old. It was created before the Internet was really a real thing. It was before the Macintosh computer and before a lot of these other things so the culture of the Media Lab has always been extremely disobedient. People jokingly called it the Department of None of the Above. We often use the word ‘anti disciplinary’ which is that it was the place where all the stuff that didn’t fit in anywhere else but still seemed like it was worth doing would show up.

What’s fascinating is that the Media Lab played a fairly significant role in the early days of the personal computer and the Internet. A lot of the early messaging came from ideas and email ideas came from the Media Lab and the community around it. An when I joined the Media Lab six years ago what I found was that my experience coming from the internet and being an Internet entrepreneur were very similar to the DNA and the ethos that we had at the Media Lab.

A lot of the ideas that I have aren’t particularly new to the Media Lab but reinforce a lot of the DNA that’s always been there. Currently at the Lab we probably have you know over 400 projects, over 85 sponsors that range from Lego to Google to Toyota.

We have just a huge variety of projects but a couple of things I think companies might find unique. One is: no one has ever had to ask permission from me to do anything. There is a huge cost of permission. If you’re an engineer or a designer and you’re sitting around on a lazy afternoon you say ‘wouldn’t it be cool if…?’ At the Media Lab, this is a mailing list conversation. Somebody saying ‘remember that episode in Star Trek where…’ By the end of the day they’re in the shop building the thing, they’re on the computer coding the thing. And in the evening they’ve got photos of it up and say ‘hey is this a thing, should I do this as a project?’ Everyone’s like: ‘what about this, have you thought about that?’ And a good project will be an emergent idea that often comes out of either faculty and students talking to each other we have the tools and the capability to basically start anything without additional funding which is the key part. You can have high degrees of permission-less innovation which is what a lot of Internet innovation was, if the cost of innovation is low enough you don’t have to ask anybody for money. Eventually when the thing gets big enough you know the companies and VCs and others will come pouring more money. There’s a parallel here, if you think about Google, Facebook, Yahoo they all had their initial products before they raised money. The VCs came after they saw some version of what was going on. The reason they didn’t they need any money and they were able to use university Internet off the shelf PC, Linux, MySQL. Most of the stack that they needed was already free or very low cost. If you think before the Internet… there’s a great book called Regional Advantage by Annalee Saxonian which talks about how Boston and this region lost its advantage in computers to Silicon Valley. Because when it costs a lot of money to do any innovation then you needed authority. You needed approval systems, you needed proposals, you needed lots of institutions. But when anybody could build an idea and it was about VCs chasing down kids who had ideas that were already built and then the business models would come later then you could invert the thing. And so that that’s what happened on the Internet.

And I think what’s interesting about the evolution of the Media Lab is that the early MIT Media Lab stuff like when the early timesharing computers were around in a lot of the tools were pretty expensive and hard to get. So everybody being physically here at MIT made sense so it was kind of this place where you had access to all these things. I think what’s changed the most is that now since the costs of innovation has gone down so much we’re able to first of all be part of a broader network. So try to connect to other things outside but also the permission-less-ness is easier to do just because you don’t need to gather all the resources beforehand.

There’s a researcher, the late Donella Meadows who talked about the leverage points in intervening in complex systems. So she was thinking about climate, poverty, the economy. And she talks about how you can go and change the parameters you can go and change the rules but ultimately the goals – and then above that the paradigm – are really what changed the system. So one of my favourite examples is the game Monopoly. It used to be called the Landlords’ Game it’s based on a game called the Landlords Game that’s I think in 1905. It’s a very old game. It was basically to describe how the idea of ownership and rents drives people to poverty and bankruptcy. And it was to teach kids how awful capitalism was. And Parker Brothers then takes the game. Doesn’t really change the rules very much but changes the goal from teaching kids about how awful rent is to you becoming a capitalist trying to drive your friends bankrupt. And that’s about changing the culture and not the rules. So in my view whether we’re talking about climate change or whether we’re talking about the output of the company it’s what people think they’re trying to do which is much more important than the rules or even the strategy.

It’s actually not a new idea. So one of my favourite quotes is there’s a guy named Andrew Fletcher who was a Scottish writer, politician and patriot. Back in the late 16 hundreds. He wrote this, he’s quoted ‘If a man were permitted to make all the ballads, he need not care who should make the laws of a nation’. And you know this is the first instance that I can find of somebody basically saying I care not who writes laws let me write the songs.

To me the influence of say punk rock or the Hippie Movement on how people behave is going to be much more significant than a particular set of rules. And this applies to labs to companies as well and everybody from you know Peter Drucker on to any management person will tell you the importance of culture.

The tricky thing is cultures are also a lot harder to change than rules because culture is an emergent thing. I mean you can’t tell people to do things even like one of my favourite things that Timothy Leary used to say that was question authority and think for yourself. And I remember going on the lecture tour with Timothy Leary where we had all these new age hippie kids coming up and saying ‘Tim what should we do’. He said, ‘think for yourself.

The problem is that just the idea of questioning authority and thinking for yourself, you can somebody… I remember going to a place and – I hate to make this sounds stereotyping – but it was a government building in, I’ll just say, a Southeast Asian country. And in Comic Sans they had this big sign ‘Be Creative’. Telling somebody to be creative or telling somebody to be disobedient is not really the way you get them to be disobedient. How do you cultivate and tune the culture in the right way. I think that’s a lot more like being a disc jockey or a gardener than it is like being a General or a sort of what people think of as a CEO. This is also not a new idea I think. Dee Hock, the founder of Visa, and others have talked about sort of Leader Followers. Leaders that lead from behind or really are trying to create an environment in which innovation and other things happen. They tune the culture and then that’s where I first started thinking about this when I was a disc jockey in a nightclub in Chicago. I remember it you know the DJ booth was connected to the manager by the bar. They would say ‘can you get more of the kids onto the dance floor and get them sweaty’ and then they’re all dancing. ‘Now get them over to the bar’ and you get them over the bar. They say ‘hey those Puerto Rican kids in the corner haven’t been dancing, get them on the dance floor’. This is pretty straightforward output that we wanted. We want people to get sweaty, we want people to drink, once they get drunk we want to get them out. The DJ by just changing the background music was able to get that to happen much better than somebody going around trying to convince these people to do that.

So for me I feel like my role at the Media Lab is to try to tune the background music, to tune the kinds of stuff that’s going on, to sort of create a place where people are happy to be, who feel like everything is is going on. And to not try to control the the exact actions of everybody but try to control the mood and the culture of the place. Again you can’t run every organisation like that. But I think especially when you’re trying to get an organisation where you’re embracing diversity and serendipity and innovation. Leading from the environment is one way to do it.

Joi, one of the things I wanted to understand was that in a world governed by routines by 10 meetings a week, 200 emails a day how do we find the space for new ideas. Someone once said to me ‘beware the busy manager’ and it’s gone beyond that, it’s ‘beware the busy everyone’. There’s no space for thought. There’s no space to fill the gaps with daydreaming. One of the things I wanted your view on is the concept of play. I’ve observed that when I play a game with people I feel more energised, more creative. I wondered your take on it. If we’re trying to design a new world of work. is play important?

JOI ITO: I think play is essential for the kind of creativity that we’re interested in. You can try to break down play in different ways but the when human beings have reactions like disgust or anger they’re all some kind of survival trait. But the idea of laughter or fun is interestingly probably connected to these learning moments when you get like an aha. It’s this moment of surprise and excitement.Because normally we don’t like to be surprised but when the surprise is connected to something that’s wonderfully useful for creativity and learning we enjoy it. Play also is something that could be otherwise somewhat combative. But if you’re in a secure feeling, like when you’re playing with your dog it might look to the outside like you’re fighting but you’re actually in play because you both trust each other that you’re not trying to kill each other but you’re actually playful.

When you’re in a lab and you’re you know asking somebody or poking somebody if you have a playful mood it’s quite easy to be critical of each other because you’re sort of jousting. And you’re not trying to eliminate your opponent, you’re trying to make them stronger. You’re trying to learn and you’re trying to be creative. Play is a really important way to also wrap sometimes difficult interactions in a comfortable respectful way.

Humour is like that too. Baratunde Thurston was one of my Director’s Fellows and he’s a very funny guy. He wrote for The Onion. He used to be a very serious black activist at Harvard and not a funny guy. And he said he learned comedy because then he could deliver really difficult things wrapped in comedy.

Jon Stewart is the same thing. They can often say things directly at the camera that you wouldn’t be able to say with a straight face so I think also humour is a great interface for very difficult to digest messages. And the other piece about play I think is important is there are some studies that show this is when you’re focused and you’re motivated by anxiety, fear or money. You can move very quickly and efficiently through a somewhat linear brute force processes. But when you have to step back and try to explore or create a space play is really an important mindset to be in. And I would add to that the somewhat mischievous culture which ties to disobedience is the idea of trying to come up with hacks that are clever or funny and also lead to a really interesting form of creativity. A lot of the really interesting projects that I see at the Media Lab started out as kind of a joke but then they turn out to be actually pretty functional and real. In order to create a environment of play I think we get back to the culture thing. I think it’s it’s not super straightforward. You can’t just tell people to be playful You have to model it. You have to give people the confidence that there’s there space to do it. But also the right kind of encouragement to do it.

I saw you wrote a blog post, it was wrestling with the challenge that we all have to balance 6 hours email a day, how we end up giving partial attention to things. Do you see an easy solution to that? How you can manage meetings and emails – and the overwhelming volume of demands coming in.

JOI ITO: So the question I think is about my blog posts where I basically throw my hand saying I don’t know what to do about the fact that I have so much e-mail and so many meetings. I end up having to give partial attention during meetings and I feel disrespectful. I really don’t know what to do. And I’ve tried so many different ways to both deal with my email and try to sort out the meeting thing. I have three people reading my emails already helping me and I tried many things. Many tools as well. But I think the most useful comment that I got was from Ray Ozzie – who developed Lotus and was Microsoft. I love Ray. He’s always very thoughtful and obsesses about these sorts of particular things. He said you’re thinking about it the wrong way. What you need to do and it’s really hard, is you need to get to the point where you are getting through your inbox everyday. Because just think about as a flow problem. If you have more stuff coming in then you can deal with every day that means you’re gonna continue to have more stuff piling up. You just need to figure out how to get down. Now that could be stop, start saying no to more things, create more bandwidth for taking care of things, delegating.

But as long as you’re creating a massive To Do list that grows faster then you’re getting rid of it you’re going to be bankrupt all the time which I sometimes did I sometimes declare bankruptcy and just delete my whole inbox and say that on Twitter. It doesn’t really doesn’t solve the flow problem.

So I’ve been trying and I’ve started resigning from boards trying to cut my meeting criteria tighter and tighter and tighter. I’m still not there. One of the things in my blogpost was ‘should I have some meetings where I don’t use any devices and I’m fully present’ and some meetings where they’re cheaper meeting so people who need my time sooner but are willing for partial attention. I divide it into two types of meeting types. I think I’ve decided that I will pay proper attention in all of my meetings but I will try to reduce the number of meetings. Now that means saying no to a whole bunch more things than I have in the past. It means making a lot more people unhappy but also as I started thinking about it, it is how should I be prioritising things?

There are a lot of great self-help books on how to prioritise. But I think you know the thing that I want to tune is: I could easily see my schedule completely full of regular meetings with people I already have to work with. But then the problem with that is you have no serendity and you have none of the stuff that we’ve been talking about this whole podcast. So I think the trick is to how do you create a distribution of enough randomness, enough young people who don’t yet have enough of a background to be able to be impressive. And how do you then also add to that the operational things that need triage and the priority. That’s really hard. Different people prioritise very differently. One of my best friends, Reid Hoffman, he’s a master at certain types of scale but he has this weird philosophy which I don’t really agree with. He calls it ‘Let Fires Burn’. He talks about this famous story where at PayPal where there were just so many problems that the customer service was ringing off the phone. People just stopped answering the phones until they got past a certain thing. Then they started answering the phones again. For him hyper focus on the top priority is the way he’s been able to scale these things which makes sense in the venture sort of situation where you can’t take your eye off the ball and this is about focus.

On the other hand when you’re in exploration mode or if you’re trying to build a personal network you can’t just let every fire burn so it’s so different people have different philosophies. I’m still searching for the right prioritisation philosophy.

I would finish by saying those are the two pieces. One is the ability to create a machine. In my case my support team, my technology so that you can execute on whatever prioritisation philosophy you have. So that you can change it and still function. And then you have to have a rigorous or a thoughtful prioritisation philosophy so that the people in your system know what sorts of things you’ll spend time on and what sorts of things you don’t need that you yourself can do that. And then there’s a bunch of theories on how to do that. I haven’t gotten there but I’m committed now to trying to get to a point where I am able to. So for every ‘no’ and every ‘yes’ it could have randomness involved but even the randomness is there intentionally.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]