Brains, hormones and time – the invisible causes of better workplace culture

I had a wonderful discussion with Robin Dunbar and his co-author Tracey Camilleri about the invisible ingredients of human relationships. Specifically the role that hormones, brain-size and time play in the connections we build. It invites us to question whether we could use those forces to make work better?

Hormones are triggered by emotional interactions with other humans. Uniquely they only tend to work face-to-face. Hormones can help us build affinity with others in a powerful way that is often overlooked.

Brain-size impacts the connections we have with those people. At the core of human experience is our closest one (or two) relationships. There’s a small circle of 4 or 5 people who sit at the heart of our lives, and up to 15 who make up the majority of our time.

And that time is critical for the strength of those connections. We spend 40% of our time with our 5 closest relationships, and 60% with the top 15. By spending time we can become close friends with people in our lives.

The Social Brain by Tracey Camilleri, Samantha Rockey and Robin Dunbar is out now.

Transcript produced by clankers, double check before citing:

Bruce Daisley: This is eat, sleep, work, repeat. It’s a podcast about workplace culture, psychology, and life. Hello, I’m Bruce Daisley. Thank you for listening. I had the biggest listening figures ever, actually last week for the podcast. So obviously an enforced absence produced a bit more appetite for these things.

I was delighted with that. Thank you for that. And if you do enjoy the podcast please do share it with other people. I never bore you with things like that. Do I never ask for iTunes reviews. To count your blessings, that’s the only time you’re gonna get it. Okay. I got a good episode today.

I mentioned when I was putting these episodes together, my objective really was to try and get to groups with how work is changing and how we can try to address it. Last week I chatted to Amy Gallo with a perspective of trying to understand. The relationships that form work and today is more of the same.

I’ve got a really fascinating discussion with two of the authors of a brand new book, and it was largely the themes of the book that provoked me into thinking that this would be helpful. The book’s called The Social Brain, the Psychology of Successful Groups. It’s by Tracy Cam. Samantha, Rocky and Robin Dunbar, and you’ll know Robin Dunbar.

He’s a former guest on this podcast. He’s famous for ideas like Dunbar’s Number, which is all about how human beings, brains are one of the limiting factors and brains form a part in the way that we. Set up and establish relationships with other people. We can only trust 150 people. We only have one or possibly two people at the heart of our relationships, five people who we spend 40% of our time with.

We spend 60% of our time in total with the top 15 people in our lives. All of these things are related to brains, but one thing that came outta the discussion and the book was a really interesting theme that to my mind. In any consideration about workplace culture often gets neglected. It was this idea that the things that determine human relationships are hormones, brains, and time.

Hormones, brains and time. And it’s so interesting because in considerations about workplace culture, I don’t think we ever have these dialogues about the human software, the human hardware that plays a part in how we form trusting relationships. But what you find from it is it gets to the heart of trying to understand what an effective group looks like.

One of the guests today, Tracy says that she observed some of this when they were curating some some business courses for students at the university she teaches at, and they observed that when the class went from 40 people to 45 people, it seemed to change the way that the people on the course were interacting with each other.

And it’s insights like that help inform this. I think the most critical thing that I took away from this is that as understanding the role that hormones, brains, and time play in human relations is really critical. And as we go on, Tracy explained something that I think is a sort of massive penny drop moment for me, is the idea that bosses increasingly need to become entrepreneurs for creating connection.

They need to be thinking all the time about the ways to. Create connections in their teams. One of the examples Tracy gives is he’s creating meals, but specifically building team meals that in her case, she said, we used, we recognized that Curry seemed to produce better sharing than other meals that were plated up and given to people because there were small plates that people had to ask to pass.

No. That for me is a really fascinating detail. In the same way that we might witness someone wedding planning, that actually creating moments of connection is increasingly gonna be the thing that differentiates different leaders and different bosses. A really fascinating discussion that I think will give you an insight into the work that maybe Robin started with his anthropology, his study of animals and the humans, and then going on and applying it, which is what Tracy and Samantha have done so.

I really enjoyed this discussion. I think you’re gonna get a lot of value from it. This is my discussion with the authors of the Social Brain, Tracy Capillary and Robin Dunbar.

I wonder if you could kick us off by just introducing who you are and what you do.

Tracey Camilleri: Till I start? Yes. Robin? Yes. I’m Tracy Camilleri. I am an associate fellow at Oxford Side Business School and somebody who’s always been interested in how do you create organizations within which people thrive. And particularly my interest has been in leadership and what do leaders do to enable that human thriving?

Robin Dunbar: And I’m Robin Dunbar. I’m professor of evolutionary psychology at the University of Oxford. And I guess my interest. Have always been social evolution in primates. Mammals in general even, but humans in particular. And so a lot of the work I’ve done for the last several decades have really focused on the nature of human friendships, how organizations work in everyday social life and.

From this point of view, my interests really have been in applying some of these ideas that have come out of the coal pit, as they say of everyday social life applying, seeing how they apply to the world of work. Which we spend, of course, a great deal of our time.

Bruce Daisley: There seems to be like an intersection of interest.

It seems Tracy, you were running courses and noticing when the chemistry of those courses didn’t quite cohere in the same way it had before. And Robin obviously you’ve come at this from a wonderfully different perspective. Originally looking at different mammals originally and how they.

Produced cohesive bonds before we delve into the substance, what brought you together?

Tracey Camilleri: I think Robin, we met about 10 years ago, but as you say, Bruce, I’ve been directing leadership programs at Oxford and elsewhere. And as you say, really my challenge was how do you in a short period of time bring together.

Strangers who are often jet lagged who are busy, they’ve got a sort of digital life calling them away from being present. How do you create high curiosity states? How do you help trust to develop in the group? How do you create a sense of tribe and. Over the years, I got better and better at it, watching what worked and watching what didn’t work.

And I thought of myself as a somewhat, a, sort of a maverick and one day I walked into, I think you were in the anthropology department then Robin, and walked into your study and suddenly there, were all these files, there was the size of wedding invitation lift, the bonding of cohorts in armies and church congregations.

And I thought, oh my goodness, you’ve been doing my science in a way I’ve been watching, I’ve been. Thinking about and micro designing, 24 hour design. I even ended up even ended up briefing the gardeners and the ladies who made the beds and the, everything mattered.

And there you were. And so I think that’s where we came together with that same interest. Me through practice, and Sam as well, who’s the third author of the book, who had been working in a huge SE top 10 company thinking about. Actually, what helps us to cohere and what helps us to thrive?

That’s my answer. I didn’t let you in. Yeah,

Robin Dunbar: no, I’m just the reciprocal of that because I’d been like I said, interested in what makes, if you like, what makes small scale societies work and always had. Wondered how and why and where these ideas that we are seeing in everyday life as where might apply to the world of business.

And on that particular occasion, the world of business work walked through my door and said, we know how it works in business. So coming together of like minds really in the perfect match.

Bruce Daisley: One of the questions that was foremost in my mind when I wanted to chat to you. A lot of people right now are saying to me things that say that the mechanics of work, we’ve got working again we’re working three days a week in the office, or we’re told we have to be in two days a week in the office.

We’ve managed this transition to a completely different way of working. People have witnessed this fundamental change, the mechanics of it, but the one thing that they generally say to me is it doesn’t feel the same. We feel like we’ve lost something in the transition. We’ve gained something. This freedom, this ability for people to adapt their home lives and their work lives in a greater balance.

But we’ve also lost something. And as a big picture question. I’m really intrigued how you would seek to answer that to them. What do you think we’ve lost? And so where would we start looking for it?

Robin Dunbar: So I think there’s, of course, there’s been a lot of interest in hybrid working of this kind. Over the course of lockdown when it was initially forced on us.

So there’ve been a number of very large scale studies that have looked at this, and they’re quite interesting in the kind of micro details of what happens. There’s a very big study by. Microsoft of their entire organization. I think looking at email traffic and so on, what that showed and we showed something very similar in a study of Big American Research University campus, what seems to drop out while you are away from.

The place of work is those serendipitous contacts that emerge in face-to-face meetings. So what seems to happen is your email traffic to your immediate group, department, or research group, whatever it is continues to flourish and indeed may even expand because you’re obviously not bumping into people in the corridor.

At work. New contacts and casual contacts seem to drop away because you’re not having, even with. Zoom type meetings, you’re not having the same kind of interaction with people. Paradoxically, what seems to be happening is people were actually spending more time on Zoom and other digital media at work than they ever would’ve done when they’d been.

Working in the office itself. So you, it looked like an awful lot of time was just being wasted because people felt they had to be on a zoom call because somebody had called for it. But most of the time they were probably sitting in the background not paying a great deal of attention to it. So there are those kind of downsides, which probably have quite important knock on consequences and just to.

Sort of point out one. Problem solving often comes as a result of somebody from somewhere else peering in over your shoulder and looking at something on your desk and going, oh, that looks interesting. I think I know the answer to that. And. Introducing a new dimension in, into the discussion, if you like, in a way that would never have happened for the group sitting around the table or the desk, because they were all thinking in the same way.

So those sort of serendipitous. Diverse views just don’t get introduced into the conversation, and as a result, the kind of blue skies, big solutions to the problems of life or whatever it may be, don’t happen. And there’s quite a lot of evidence that really, that’s very important, even in face-to-face, the face-to-face world, that it’s the casual interactions that seem to matter more both in.

The research world and in the everyday functional world of most businesses that seem to be important, there are potential losses, I think, which have to be balanced against the benefits that accrue to you as an individual, being able to avoid the dreadful commuting costs and pressures, stresses, as well as the financial costs.

Being able to do things like take your kids to school and pick them up at a decent hour and put them to bed, and all these kind of things, which long distance commuters miss out on,

Tracey Camilleri: Just to respond. Bruce, you on the level of practice and what has been lost? We were approached by a company who had hired half their people in lockdown about 250 people, and they said, goodness, we don’t.

We don’t know one another. And yet, belonging and a sense of connection’s hugely important to us. And they asked us to design a kind of cultural gathering. They wanted everyone from the receptionist and the person who made the sandwiches to the. Chairman to be involved. They said, we don’t want it to be a festival or a party.

We want it to be celebratory, but we want it to be about learning and learning together. And to create a sense of belonging because we’ve lost it. And actually we use the seven pillars of friendship. Right at the beginning, people were nervous about this. This was. Just after, after lockdown had finished.

And so we actually paired, all the people who were fell runners together on the first day, all the people who were embroiders and so on. And then on the second day, we mixed them with the most, the people who. But most different in the organization with the idea that they would discover each other and the chairman actually said, we won a year’s worth of culture back in a week.

It was a very intense week. But I think to your point, we are noticing now I don’t think hybrid will go away and we are noticing that. Prescient leaders are developing social strategies with the same kind of rigor that they’re looking at financial strategies or or digital strategies and thinking if we only get our IT department together once a month, it needs to matter.

It needs to matter. We can’t do the same old things in person that we are doing as we are doing now virtually. So I, and I think people are really thinking about this and you say, Robin, about the younger generation. We’re doing some research at the moment about Gen Z and actually they want to, many of them want to come into the office.

One young chap said. I go in on a Friday ’cause no one else is there because the finance director is there on a Friday. And he asks me how my week has gone and that actually, that’s important, the incidental learning, I’m interested in how people learn that comes from just sitting next to someone else not getting that virtually.

So I come back to your point Bruce, I think there is quite a lot that’s lost in the magic of. What we’re doing now.

Bruce Daisley: One, one thing I really took from the book was a really simple framework that made me reflect on different circumstances. And I think at one stage you say our interactions are shaped by three things, our brains, our hormones, and time.

And that was really intriguing. I’ve, my background is I’ve worked in Silicon Valley firms and quite often when they describe workplace culture, it’s like a wiring diagram. It’s like the highway code. It’s the mechanics of how people interact with people. And this human, this human software playing a part would be a complete mystery to them.

’cause it’s, where is it on the map? And I wonder if you could just break down those three things then. How do our brains, our hormones, and time contribute to the experience of work as a social phenomenon?

Robin Dunbar: Okay. In very simple terms the issue is that the number of people we can maintain meaningful relationships with is limited by the size of our human brain.

So that puts very specific numbers on it. It seems, if we get those numbers right in an organization, organizations just work better. At least bear this constraint in mind. This is part and parcel though of the hormonal mechanisms that are involved in creating and maintaining relationships, friendships, if you will in everyday life.

And these. Primarily involve the endorphin system in the brain, which is part of the brain’s pain management system, but is deeply embedded in the way monkeys and apes and humans create their friendships. The triggering the endorphin system by a variety of activities, including. Yeah, and it’s storytelling and eating together and singing and dancing together and laughing together.

These kind of things build this sense of belonging and trust in other individuals. So you’ve got your number set by your brain, and then how well that number coheres or those individuals in the group cohere is dictated by the hormonal system. Again, part and parcel of that time is essential. You thereof.

Fixed amounts of time, which you need to devote to building relationships in order for them to get off the ground. Otherwise they’ll never quite build into something meaningful. This is a reflection of what, what goes on in everyday life and. It seems these things really have to be done face-to-face.

The worrying observation that came out of lockdown was how many new starters started their jobs and then left before they’d actually met anybody else face-to-face in the organization. You can’t create this sense. Belonging and this sense of trust and bondedness that’s created, if you like, by the village, the workplace as a village that makes the thing buzz and work efficiently and fast in the way that a well organized social community should work and can work.

If we get the chemistry right. But I think the message here though for Silicon Valley is throw away the di the wiring diagrams, because if you try and put this down into sort of simple algorithms, you’ll get it wrong for sure. It’s the one thing I’ve learned in doing research on and studying and teaching about human behavior.

You can explain to people what happens in considerable detail but. If you want that sort of bonding process to work effectively, you have to switch your mind off and let the human psyche take over completely unconsciously, because the moment you start thinking about it consciously, it all falls apart.

So it’s the key, I think, and I’m sure Tracy would agree here, is engineering the right kind of environment and ambience in which these things just. Develop in their own natural, organic way, rather than trying to force the pace with which they happen. I think that’s, the message is very clear. You’ve gotta do it very subtly because once people start to try and consciously think, oh, I’ve got to do this at this time, and that at that time, the whole thing just seems to fall apart.

We can’t do it very well.

Tracey Camilleri: I think that’s right, Robin. But I think there are ways in which you can fast track this. This virtuous triangle. And you’ve talked about eating together. We did over 50 interviews for the, with leaders from, heads of medical supply chains in Nigeria to Army generals and so on.

And we certainly, if we’re doing. Have a really tricky meeting. We will begin with a structured meal rather than often it’s the other way around. You end with it if the things go well, but actually it changes what happens. Fear as well, a shared little lip of fear. Bizarrely on programs we’ve experimented with inviting people simply to bring.

Any poem, this is not Oxford literary criticism and just read it in a small dinner party to other, a small party to other people. That act, which, seems to be full of fear for people actually reading a poem. Completely changes the conversation for the rest of the week. It’s a bizarre thing.

It’s like a sort of a Harry Potter porthole. We do, instead of workshops, we do workshops. Just walking in Synchrony together and talking about ideas or questions that, just the rhythm of doing it. Music a lot, singing Sam, who we wrote the book with, worked in the South African government during, a really.

Really difficult time. And there she really experienced the power of choirs of people singing together actually. So I think there are ways, we’ve worked quite a lot with Owen Eastwood, who wrote the book Belonging and he says. Stories told around a bonfire at night have much more heft and re resonance and we will usually end in the woods with a bonfire.

So there are things you can do that fast track. We did discover six conditions that thriving teams seem to have, which are, were present in balance in, in every team. And those were things that we’ve been talking about so far. That sense of connection, the possibility for friendship culture, that the sort of stories and the rituals that, that people actually need purpose and values.

The ability to learn. We hate being held still, I think, and not being able to. To progress these foundational conditions and a sense of belonging is absolutely key.

Bruce Daisley: What I love about some of the way that you’ve delved into that is that there’s been a degree of a skunk works of working things out and fine tuning them.

So what I loved Tracy, was the detail you gave of how. When your class rose from 40 students to 45, which you might think superficially, pretty much a rounding era, and it changed the dynamics. I think you talk a lot about the most, the biggest number of people that you can have in a conversation, I think is four or five.

I think five is where it’s, it breaks. And I loved the detail that you’ve mentioned there, Emil, that kicks things off. But you said very intentionally you’ve learned that. Curry is a good meal because they’re small plates that invite people to ask to pass items over. And what I love about all of that is that there’s a very precise architecture of working out.

If our objective is to be an entrepreneurial to, to facilitate interactions, then we can’t just say. We’ve arranged a meal. We can’t just say we’ve arranged a group who are gonna get together. It’s to some extent, it’s about being the leader’s job a, a modern contemporary leader’s job is thinking about how they can create these moments of connection where maybe in the past we got away without doing it with that degree of precision.

I wonder if you could speak about that.

Tracey Camilleri: Absolutely. I think a leader’s job at the moment, particularly is the job of being a social designer. Actually. These things don’t happen. Just, through serendipity. We are not able to, as Robin said, bump into each other and, have brilliant ideas.

We’re here, we are on Zoom the whole time, and I think those. Acts of design, so on. Yes, we always begin with a curry because you have to pass all the small plates and talk to one another. We even think about the size of the tables, so that you can, you are how many people you can talk to, never have a table too fat, that you can’t talk to the person opposite you.

And then on second day, we’d always do a kind of street food, which came from all the countries or as many countries as possible of the people. Participants so that they get a chance to tell stories, which are really foundational stories about their culture, about their food and if we didn’t do food, we’d find wine or whatever it was from those so that we flipped it.

It was all about them. They were participators. We’d think about the tone how to connect with people before they came. And we found that by fine tuning all of these things. Busy people didn’t drop out beforehand because they had that sort of personal connection. We, back to your point about size, we were really bewildered that, we had a waiting list.

One wants to make money, I suppose it seemed, let’s go up, let’s increase the numbers. And what happened, because we only had a limited period of time, was that the group immediately split into two. It was a really bizarre thing, and we thought, what is happening here? And in the small groups, the small tutorial groups, there were seven in each of them.

And the tutors were constantly closing down the talk. They were constantly saying, I think we’ve gotta move on. And it went okay. But none of us enjoyed it. It felt like work. We did it one more time, and then we said, no we’ve got to really think about scale here and what, what’s the right scale for what we’re trying to do.

So we cut back, which of course difficult when one’s trying to, trying to be profitable, but it mattered.

Robin Dunbar: And this I might point out, was before Tracy and Sam had asked me about it. So this is serious science being tested before the answer was found.

Bruce Daisley: Can you explain to me that number that we’ve talked about, sort of conversation ends at five and maybe if you could explain the sort of the ripples.

That go from one and a half to five to I wonder if you could talk through the mechanics of how our brains determine the intensity of connection. Yeah. Okay. Let me start

Robin Dunbar: with the conversational one. ’cause I, it always just intrigues me. We did actually discovered it. By accident some years ago watching what went on in conversations, and we discovered that every time a social group sitting around a table at a pub or at a reception maybe got above five, it mysteriously suddenly broke up into two conversations.

There are several contributory components, one of which is you can only have one speaker at a time and in a conversation. Everybody else has to remain quiet. For a con conversation, to get bigger than about five people, effectively, it has to become a lecture. So that, we do that we make those arrangements and everybody abides by some unwritten social rule, which says, you sit and listen quietly, otherwise the whole thing just falls apart.

If you think about it a big committee at a board gathering, as it were, if you don’t have a chairman there to, keyboard or, and stop people talking, the whole assembly breaks up into a number of small conversations, which gradually get louder and louder. And the other part of the problem is.

That it’s very difficult to hear what somebody is saying across the circle. Once it gets bigger than about four or five people, you’re just too far away really to hear at normal voice levels. So you start shouting, which is why noise levels get bigger and higher in, in receptions and the like as more people are involved.

So all these things serve to limit conversations and this natural grouping is so strong that. You experience it even on, on places like Zoom. Zoom very often ends up being dominated by about four people, and it’s usually the four people with the loudest voices and the rest retreat into the depths of their news feeds or what’s going on in the street outside the window, while vaguely listening to what’s going on.

It’s important to bear this in mind. Of course, it has dramatic impacts in terms of work. Groups. ’cause if you have more than about, let’s say four or five people in a small scale work group working on a problem, it’s very difficult for them to engage in conversation with each other at the same time.

And to manage the processes of contributing. Another reason why this limit is that the bigger the group, the less airtime each of you gets. And after a while you want, I wanna say something, let me in. It all starts to get very annoying. So there are those everyday limits, which you just have to look around at the next reception or evening in a pub to see this.

It’s quite magical. Our social world more generally consists of a series of very discreet layers or circles. Of relationships, usually in our kind of everyday world, this consists of about half family, extended family members and half friends in the normal meaning of the word. But we always treat them together as one, much the same thing.

They’re just your social relationships. Now the way this seems to work is there’s a kind of outer limit on the number of relationships which you can maintain coherently at any one time. That’s about 150 people. It’s varies around that, but on average it’s always about 150 people. And then as inside that you have a series of layers.

So your social world looks a bit like the ripples on a pond when you drop a stone in, if you like. So if you imagine yourself as a stone, you are surrounded by a series of. Waves or ripples going out from you, which are very small near you, but very high. And as they go further and further out they get bigger and bigger, but the height of the wave gets smaller and smaller.

So the size of the circle represents the number of people and the height of the wave itself represents the emotional closeness you have with those people. And these layers occur at one and a half, five, which clearly. Tucks into the conversational constraint. Fifteen fifty, a hundred fifty, and we know actually that they go on beyond that to 500, 150 and 5,000.

After 5,000, you become complete strangers. You have no idea who those people are, but everybody within that player. You’ve seen them before, either in a photograph or in the street or face-to-face in some way, so you recognize them. You might not know who they are, but beyond 5,000, they literally are strangers.

But these, the quality of the relationships you have with these people depends on which circle they lie in. Clearly the. Circle of one and a half is your romantic and intimate relationships. And this is probably not at work in the majority of cases, but beyond that work.

Colleagues start to filter in because obviously you do establish good friendships with people at work and you see them socially afterwards. We think most of your work colleagues probably sit in the layer of acquaintances, which sort of goes, sits outside the 150 and runs out to about 500. So characterize them as people who you’d go and have a pint with them after work maybe, but you wouldn’t invite them home for.

Big party, and you certainly wouldn’t invite them for those kind of once in a lifetime events like a Bar mitzvah or a 50th birthday party or a wedding or, and they wouldn’t turn up to your funeral for sure. But the people inside the hundred 52nd or hundred 50 of them would and turns out that 150 is a very characteristic size for wedding guest lists both.

Here and in the, in America in the inner layers as you come in, are characterized in different ways and serve different functions for them. So you’ll, that inner layer of about five we refer to as the support league or the shoulders to cry on friends. They’re the friends that will come and pick you up when your world falls apart.

They’ll drop everything to come and help you out. The next layer out at 15 is sometimes those the sympathy groups. That’s your main. Social circle as it were, that you draw on most regularly for social events. The 50 layer, I think is your, I don’t know your big-ish birthday party event, if you’re gonna throw a yard, a barbecue.

In your back garden you’d probably draw on that 50 layer most. The quality of the friendships varies. What they will do for you varies the closer into to you are in those circles, the more willing they are to drop everything and help you out should you need it. And, at the end of the day.

The world of work depends on those, precisely those kinds of favors. So if people aren’t if your work colleagues aren’t distributed through those layers it’s like trying to get a favor out of a stranger.

Tracey Camilleri: Going on from what Robin was saying, one of the things that.

Perhaps surprised us out of our interviews. Just thinking about the ripples as they work at work, was that people seem to lead in different ways at different scales, and maybe that’s just an obvious thing to say, but at five. You don’t need a leader. You may need a, you may need some permission to just go at pace and not necessarily, deal with all the bureaucracy and they’re great for creative teams, crisis teams, and so on.

But there was a sense that leadership at that level is about standing back, around 15. People talked about facilitative leadership, and again, maybe this is obvious, but I don’t think we train people necessarily for these skills. We train people for broadcast, for presentation skills or speaking skills.

For listening, for conversation, for mediation, for tho, for convening those sorts of skills. Absolutely key because what you need there is diversity really in that group. If you’re gonna make decisions at 50, and we noticed 50 was quite an interesting number for entrepreneurs or startups.

It was the num, number at which you couldn’t hold it anymore in your head. And that, you started to feel sentimental about the old days and you start a new layers and you had to start to think about the way information passed around the system. You had to focus on the message, receive, not the message.

And 150 as Robin says, beyond that, the kind of weird stuff happens. It’s the tipping point. It’s the point at which we becomes us and them as Wl Gore says. And there beyond that, you have to accept as a leader. There’s a symbolic nature to what is projected upon you. People’s hopes and fears get projected upon you as a leader actually, ’cause they don’t have a real relationship with you.

But there’s real power as well in what you can do symbolically as a leader at those points. So I think people sometimes underestimate that. So we’ve been interested actually, that we don’t necessarily train people in the skills that are needed to lead in different ways at different scales.

Bruce Daisley: Two intriguing questions following that, the, you evidence, one piece of research that talks about the ideal size of an organization to maximize sociali to maximize social socialization.

So you, I think you said somewhere, an organization that’s sixty two, a hundred twenty people or something in that region that, that tends to have cultures where. People socialize with each other and definitely if anyone’s ever worked in an organization that goes from below that size to above that size, they’ll recognize that, the, there’s a degree of factionalization that takes part.

I’m intrigued in that the, there, there seems to be a sweet spot. And you mentioned the Gore company that really bakes this. Limit and Amish society as well. You mentioned that, that bakes this limit into their structures. IWI wonder if, if anyone’s thinking about this for their own organization, what advice would you give based on those numbers?

Tracey Camilleri: I think it is a moment when people are really looking at the structure of organizations. ’cause the old kind of pyramid, it is actually a brittle beast. Particularly in a complex system where change is coming from beneath or from, it’s not coming from the top cascading down from the top.

So people are thinking in more. In flatter, more f fraternized, honeycomb sort of ways about the structures of their organizations. And goodness, there are huge organizations that are very successful. Again, our co-author Sam worked for SAB Miller, huge fsie top 10 company.

And now taken over. They had a culture actually, that was actually, everyone came together around, around a beer in sort of five or five 30 in the evening, and a real culture of friendship. And I’ve been amazed that it hasn’t existed for several years. But the diaspora of relationship, how it’s lasted so long, is extraordinary to me.

So back to your question. Bruce I think it’s not necessarily about absolute numbers, but it’s about how you conceive of organizations, I think, how you distribute leadership. So I don’t think I know WL Gore felt that every 150 and needed to start again. But I think it’s more about, creating opportunity for more powerful relationships within large organizations and actually leadership. And it lives in the relationship. It’s not about individuals or mastery or position. It is about. The strength of relationships. I dunno, Robin, what you’d say. That there’s an ideal of ideal size of company.

Robin Dunbar: The answer is no, because in principle, this fractal structure of the social world allows you to build almost infinitely sized if you do it right in the right way. Infinitely sized organizations the key. Is trying to maintain this fractal structure. After all, that’s exactly what the army do. All armies around the world, all modern armies are built up in this fractal way where small units on the ground are gradually.

Brought together in, in larger and larger groups, and they maintain this structure of 15 fifty, a hundred fifty, five hundred 1500, 5,000, 15,000, 50,000 universally. And they’ve worked that out just by practice as it were, of what actually works given the constraints of what they’re trying to do, what their function is as an army in the battlefield as well.

Bruce Daisley: And you say a lovely thing there. You say you quote a retired general and you say it’s generally not their countries that soldiers die for. It’s the members of, I guess it’s the people they share a temp with

Robin Dunbar: or the company. It’s the

Bruce Daisley: members of their small group. Yeah. And so it’s just an important reminder.

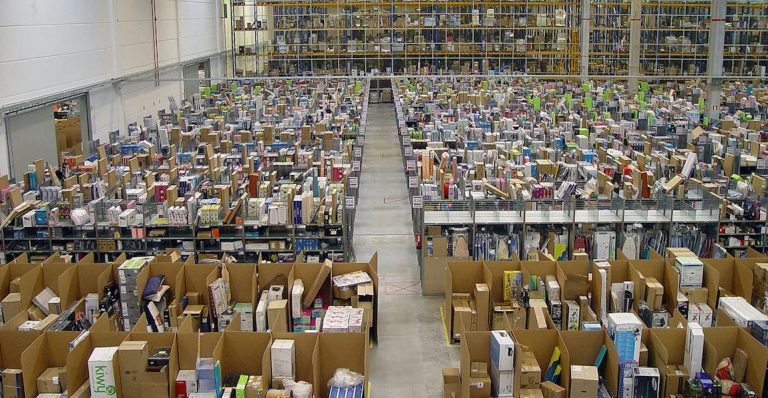

There was one thing that really. Connected with me. I read a couple of weeks ago about the plight of warehouse workers who increasingly warehouse workers were having so little time allocated for personal interactions that they were finding work incredibly isolated. And you lie side byside to different groups, railway workers and factory workers.

And you say how factory workers superficially they might be suffering from a harder working. Experience ’cause they’re working nights, they’re working antisocial hours. But because their days or their evenings, their working days are filled with laughter and connection and joking with each other, the mental health experience of them was significantly better than people who worked in warehouses, who reported feeling disconnected from their customers, disconnected from their colleagues, and disconnected from the job that they were doing.

And it really struck me that sense of connection might seem. Like a triviality that doesn’t exist on the business. The business plan, it doesn’t exist on the balance sheet, but it, for me, it spoke to the importance of these elements of humanity and secondly, how critical they are for business objectives.

Tracey Camilleri: That, that was some work done by a company called Liminal Space. And it was called Night Shift. Yes. Looking at. People doing night shifts, and I think you are right, Bruce. It wasn’t only that sense of connection and camaraderie, but also there was a sense of meaning out of their work. They felt they were actually repairing, I think they were repairing railway rail line, and they felt that they were, doing, they were bringing, they were making.

Things safer. There was a sense of pride in what they were doing and connection. And I think, this is Robin’s written hugely about this and this, there was a study, I think today published by the BMA about, the effect of friendship and connection on people’s health. As a, I think, Robin, you always say, don’t you, if you want to give up smoking don’t guess a nicotine patch.

Find yourself a no, a non-smoking friend. And, friendship at work as well is so important. The World Happiness Study also talked about that’s, need to have friends at work and yet do we make conscious space for it? Isn’t it something, oh, it’ll just happen naturally, but I think those are the things, back to the first question you asked us in this podcast, which is what has been lost?

I think some of those spaces and opportunities have been lost.

Robin Dunbar: The danger here is, or has been, I guess we might say, that other interests in terms of how a business and organization is structured and works and its function have intervened to drive their organization in ways that aren’t necessarily very productive.

And this is, in part this is because a lot of our perception of. The efficiency or value of an organization is in terms of accountable outputs as they were. So you can count up how many sales units you’ve sold, or what the profit margins have been and so on, so forth.

Which is fine, we do need to know about these things and keep an eye on them, but they don’t necessarily increase. The effectiveness or efficiency with which an organization works. And the problem as we argue in the book really is that because that’s very difficult, that social metric is very difficult to figure out and count up in simple numbers that you can put in a PowerPoint presentation to the board.

’cause that’s very difficult. By and large, everybody from the accounts department to the work study folk have ignored it as rather trivial. And our point is actually, no, it’s probably the most important feature. You need to think about if you want the organization to function efficiently and do its best.

It is not the profit line you need to look at. It’s actually the relationships between the individuals. And what’s interesting is we’ve shown recently that these numbers, and particularly 150, are what are called attract in, in the business. They’re numbers where the system naturally gravitates to because.

The system, the network. This is in terms of the structure of networks. The network works much more efficiently. Information flows around them efficiently. Now, if you have a board that imposes the different kind of structure on the system, it’ll disrupt those efficiencies. And by, by making the groupings, as it were the of the various layers, the wrong sizes, if you can restructure it all so that there are.

They hit these numbers 50 15 150 and 500 and so on. What you’ll find is that the flow of information around the system, however that you like to measure that, whether it’s bits of paper flying or people talking to each other or the bonding processes involved will just work much better.

It’s a medical process in a way. But it’s remarkable and we show mathematically that this is so there are very good reasons for trying to organize the structure of an organization into these characteristic blocks, as it were, and have them build up this sort of hesitate to use the word military like structure.

But the military got there before us, so give them credit. If you are organized so that your bottom groupings are gathered together in, into ever bigger groupings of about these numbers, the whole structure will work much more efficiently for you, and your profit line should be higher.

Tracey Camilleri: And your point about measurement, we only value what we measure. In the 19th century we took air quality for granted. We didn’t measure it water quality and. Just because we can’t see relationship, just because it seems to exist in the spaces in between, I really do believe that there will come a point where we will be able to measure the social quality of organizations, where we will be able to take.

Take it seriously. And we need to, particularly now, what is it, $50 billion being spent on wellbeing and loneliness and those sorts of really you. Aspects of people’s mental health in the workplace. This is a moment where we really do need to sit up and take notice.

Bruce Daisley: I fully agree with you, but I do subscribe to Goodheart’s Law, which is Goodheart’s Law is any measure which becomes a, any good measure, which becomes a target ccs to be a good measure. And there, there is some fundamental conundrum we’re faced with. We’re almost outta time. I just wanted to ask one question specifically, Robin, you’ve also written a book this year, or it just came out about religion and I just, I wonder if you could bring the religious to the secular, what could any organization learn about religion?

I’m specific I’m priming the pump here, but I’m interested in how religion uses ritual and, I think it’s the old phrase, if you wanna make someone see God, get them, make them. Get down on their knees and pray. First is I wonder what? Yeah. Rituals we can learn from religion.

Robin Dunbar: Essentially the book is an extension of the friend’s book and the social brain book really, and just saying look, these things apply in the world of religions as well as an everyday life.

So if you look at what the optimal size of congregations is, lo and behold, it’s about 150 people. If it’s too small, it doesn’t work quite so well. If it’s too big, it becomes fractious and breaks up of its own accord. It’s clear that I suppose religions are in a sense, a natural part of our psychology by and large, and we’ve had a lot of practice at them, and I think it.

What we see in religions is simply the expression and the exploitation of exactly these kind of organization, same organizational principles, the use of storytelling and stories, foundation stories that explain why we. Belong together. What it is that we’re here for, what our purpose in life is in what good are we doing, as it were?

The rituals of interaction that people engage in, in services, the kneeling and the standing and the singing, and occasionally the dancing, and even in some cases the laughing, all these things and the eating together, all these things. Build this sense of community. So actually this book is arguing that the origins of religion lie in trying to create, or our ancestors attempts to create bonded, well-functioning small scale communities.

And in some sense, that’s. The root of the problem. It’s very a good metaphor actually for organizations. We can use religions, use the same processes to build ever bigger mega religions up to the big ones we see now, but actually they were designed to handle communities of 150. So on consequence of that is.

You get this bubbling up from underneath of breakaway cults and sex, who, are very often built round, charismatic leaders who’ve discovered a new truth of life, as it were, and are very attractive then to the members. But they’re very personalized little groups of, max of 150 people and they either survive and break away and.

Become new religions eventually or they get suppressed by the mother church who doesn’t like them.

Tracey Camilleri: And if I could just do a watch out here so we don’t end on the note that we’re trying to set up cult here. Nothing comes for free in biology, and I think what we’ve learned, and even in the acts of writing the book.

Is that there are times when you need to go with the grain of our kind of inherited psychology and biology, and that actually by going with it that you know, rather than going against it back to your attract and so on, there are huge things we can accomplish, but at times we have to go against. A sense of belonging is great, but if we start to drink our own Kool-Aid and believe that we are, invulnerable and that, get cultish, it’s not so good.

So I think it is a question of working with and against and. But you are right. Of course. The storytelling, the eating all those sorts of things hugely important.

Bruce Daisley: If you were to have final one, one final word and you’re wonderful at packaging up the lessons that people might take from this, but if you were to give people listening to this one way that they might think about applying the.

Implications of the social brain to how humans interact and how teams work. Is there anything you’d leave us with?

Tracey Camilleri: I think it’s a moment. I think this is such an interesting moment for people to be thinking about how they bring people together and how they make it matter. Again, we spoke to Theodore Zelin and he ended up by saying, is it not the job of business to create experiments to provide something better?

For young people and I feel hopeful about our ability to learn from this moment and to create environments where people are productive. They have impact, they, innovate, but they’re also happy and healthy. And I think that’s what we are trying to explore. And it’s, there’s a whole toolkit in the social brain.

Robin Dunbar: I I pick a, take that a bit further even actually, and just point to the fact that we have this kind of pandemic of loneliness among the 20 somethings in particular, the new job starters, basically coming into a strange city where they know nobody other than the people that, that they mix with at work.

And that’s been going on for. 20 years probably, and just getting worse and worse. And my, I, what I would simply point out to business organizers as they were leaders is that’s a huge health cost for you because the biggest predictor of. People’s likelihood of falling ill, getting depressed, getting physically ill, contracting diseases of all kinds, and therefore having to take time off work is whether they’ve got friends or not.

So if they’re unable to build friendships and build a social world at work, particularly the young ones coming in from, graduating from university, one end of the country and coming, to their first job somewhere else in a big city where they know nobody you would increase your productivity enormously just by solving the friendship problem.

I don’t say solving the friendship problem is the easiest thing to do, but. The more you think about it and the more you try to find solutions to that, I’m sure the profit margins will rise Inexorably,

Bruce Daisley: thank you so much. Such a timely conversation. I’m so grateful for all of the insight and all of the provocation, actually, so thank you, Tracy.

Thank you, Robbie. Thank

Tracey Camilleri: you, Bruce. We really enjoyed it. Great

Bruce Daisley: pleasure as always.

Thank you to Tracy and Robin. Samantha, the co-author wasn’t able to join us, but she’s she’s obviously a contributor to the book. I’m really grateful for your company today. You’ve got a few more episodes recorded and ready to go, and so you’re gonna be seeing those in your feed pretty soon.

But if you have enjoyed this or you’ve got any value from it. Or even if it’s provoked some discussion, please do get in touch. You can do that via the website. That’s eat, sleep, work repeat.com and you can connect with me via there and send me your thoughts. Always grateful for your company.

Thank you so much. I’ll be Bruce sadly. See you next time.